- Report

Plastics, Profits and Power: How petrochemical companies are derailing the Global Plastics Treaty

Overview

Plastics, Profits & Power exposes how fossil fuel and petrochemical companies are working to derail the Global Plastics Treaty, the world’s most ambitious effort to end plastic pollution.

While lobbying heavily to weaken the treaty, corporations like ExxonMobil, Shell, Dow and INEOS have expanded plastic production, locking in decades of future pollution.

Industry lobbyists now outnumber many national delegations, scientists and Indigenous groups, and their presence creates a profound conflict of interest.

Without decisive reforms, the treaty risks being captured by the very polluters it is meant to regulate. Greenpeace calls on the UN to ban fossil fuel lobbyists from the talks, embed strong conflict of interest safeguards, and ensure meaningful participation for frontline communities and independent experts.

JUMP TO SECTION

Executive summary

Plastic pollution is harming health, accelerating social injustice, destroying biodiversity and fuelling the climate crisis. Yet without urgent intervention, plastic production could triple by 2050. The Global Plastics Treaty, entering its final negotiation round in August 2025, represents our best – and possibly only – chance to change course.

But industry data obtained by Greenpeace UK reveals that since the treaty process began in November 2022, just seven of the fossil fuel and petrochemical companies sending lobbyists to the talks – Dow, ExxonMobil, BASF, Chevron Phillips, Shell, SABIC and INEOS – have produced enough plastic to fill an estimated 6.3 million rubbish trucks. That’s five and a half trucks every minute.

Over the same time period, they have also expanded their capacity to make new plastic by 1.4 million tonnes, locking in future plastic pollution. The UK’s biggest plastic producer, INEOS, has increased its production capacity by over a fifth since November 2022.

This report exposes how some of the world’s largest petrochemical companies are expanding production while flooding the treaty negotiations with hundreds of lobbyists in an effort to weaken ambition and shift attention onto false solutions like chemical recycling.

With plastics increasingly central to Big Oil’s growth model, lobbyists have attempted to dominate the negotiations while positioning themselves as partners in solving the plastics crisis. Lobbying to weaken the treaty is not a side issue – it is a core business strategy.

Dow and ExxonMobil – two of the world’s biggest single-use plastics producers – have sent the largest number of their own delegates to the talks, as well as being heavily represented by industry associations. This reveals how those with the most to lose from meaningful regulation are working hardest to obstruct and undermine it.

Over the course of the negotiations these firms have made staggering profits from plastic production. Dow alone has earned an estimated $5.1 billion from plastics – while sending at least 21 lobbyists to the treaty negotiations.

There is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations: the same fossil fuel and petrochemical companies that profit from plastic pollution are being allowed to shape the treaty designed to end it.

To protect the integrity of the Global Plastics Treaty, Greenpeace UK, Greenpeace International and our allies are calling on the UN to:

- Ban fossil fuel and petrochemical lobbyists from plastics treaty negotiations and future Conferences of the Parties.

- Embed a strong conflict of interest policy in the treaty text.

- Ensure meaningful participation for scientists, Indigenous Peoples, impacted communities and public interest groups.

It’s time to kick polluters out of negotiations and ensure the treaty delivers on its promise – to end plastic pollution for good.

The stakes

What the Global Plastics Treaty is fighting for

In August 2025, the sixth and probably final round of negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty will take place in Geneva, Switzerland. The treaty is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to tackle plastic pollution at its source. It aims to regulate plastics across their entire lifecycle – offering a pathway to curb environmental destruction, reduce fossil fuel dependence and protect human health.

But this ambition is under threat. Fossil fuel industry actors are lobbying for weaker terms and opposing binding production limits while promoting downstream measures like recycling and waste management. Without upstream controls – particularly limits on plastic production – plastic pollution will keep rising, along with its devastating impacts on the climate, nature and health.

A crucial opportunity to end plastic pollution

In 2022, the UN Environment Assembly launched negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty – the most ambitious international effort to date to tackle the plastic pollution crisis. Unlike previous initiatives, which focused narrowly on waste, this treaty adopts a full lifecycle approach: from plastic production and design to consumption, disposal and pollution in all environments.

This shift reflects a growing understanding that addressing only the waste stage ignores the root causes of plastic pollution. Plastic output has surged for decades, driven by fossil fuel and petrochemical companies, while waste systems struggle to cope. This has resulted in increasing pollution, with marginalised and low-income communities disproportionately exposed to its toxic impacts.

Urgent action is needed to put limits on plastic production. As the UN Environment Programme has repeatedly emphasised, we must ‘turn off the tap’, not just mop up the floor.

If it includes strong, binding upstream measures, the Global Plastics Treaty could become one of the most consequential environmental accords since the Paris Agreement.

How industry is pushing back

However, the treaty is under threat. Major fossil fuel and petrochemical companies and their industry associations have exerted a strong influence on the negotiations, apparently pushing to narrow the treaty’s scope and shift responsibility downstream.

They are advocating for:

- No caps on virgin plastic production.

- A focus on recycling and waste management. This ignores the fact that recycling currently processes only around 9% of plastic waste, and even by 2060 is projected to reach no more than 17% – far below what is required to handle current, let alone future, levels of plastic production.

- Chemical recycling as a core solution,, – despite it being expensive, inefficient and often more polluting than conventional methods.,,

These positions serve a profitable business model built on ever-expanding output, while often shifting responsibility for plastic pollution onto consumers or governments in the Global South, who have done least to cause the crisis and are least equipped to manage it.

Why this matters

Plastic is a fossil fuel product: 99% of plastics are made from oil and gas. As the world begins to move away from fossil fuels for energy, oil companies are banking on plastics to sustain their business models.,

Without intervention, plastic production could triple by 2050. It is already projected to account for 45% of net oil demand by 2040. This would mean more pollution, higher emissions and greater harm to human health – particularly for communities in the Global South, who already bear the brunt of these impacts.

The plastic lobby

Pushing pollution

Powerful fossil fuel and petrochemical companies are working to derail the ambitions of the Global Plastics Treaty – not just by lobbying for weak outcomes, but by expanding plastic production even as talks are underway.

Their strategy appears to be twofold: flood the process with lobbyists, and build the infrastructure to lock in future plastic growth.

6.3 million rubbish trucks – and counting

Since negotiations began in November 2022, just seven of the top fossil fuel companies sending lobbyists to the talks – Dow, ExxonMobil, BASF, Chevron Phillips, Shell, SABIC and INEOS – have produced enough plastic to fill an estimated 6.3 million rubbish trucks. That’s five and a half trucks every minute.

And they’re not slowing down. These same companies have expanded plastic production capacity by 1.4 million tonnes over the same period.

These seven companies are among the most prominent corporate lobbyists in the treaty process, and have sent a combined total of 70, representatives since talks began.

A flood of lobbyists – and enormous influence

Lobbyists acting on behalf of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry have flooded the Global Plastics Treaty talks, and their presence has increased with each round of negotiations.

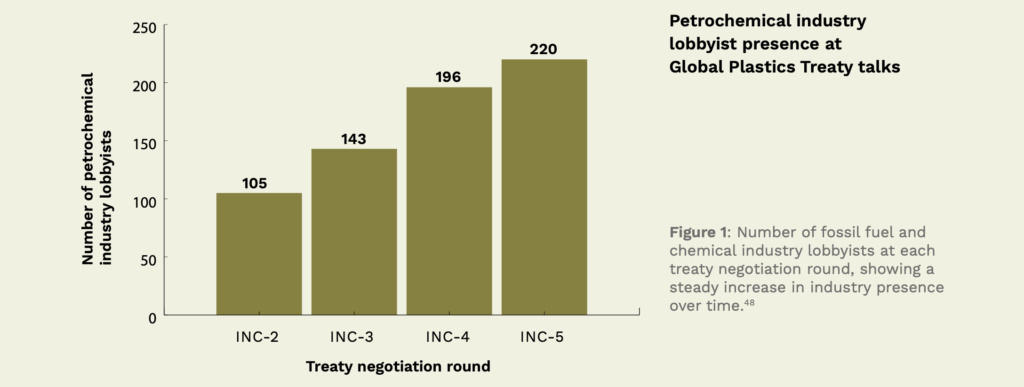

At INC-1 in Uruguay, corporate delegates and trade associations were already inside official negotiating rooms. By INC-4 in Canada, 196 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists were registered to attend – more than the smallest 87 country delegations combined, and three times the number of independent scientists (Figure 1).

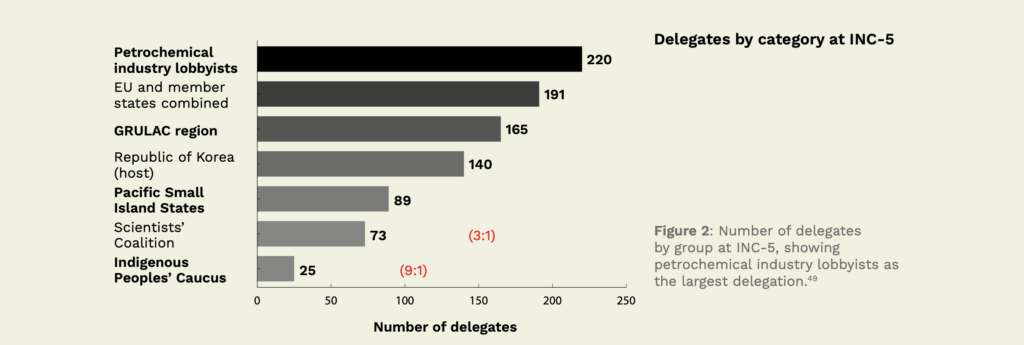

At INC-5 in South Korea at the end of 2024, a record 220 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists were present, making them the single largest delegation at the talks; more than the EU and its Member States combined. Lobbyists also outnumbered the delegates from the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty by three to one, and representatives from the Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus by nearly nine to one (Figure 2). This meeting, which was meant to be the last, failed to achieve a deal and negotiations were extended into 2025.

Even these numbers understate the true influence of the plastics lobby because industry representatives are often embedded within the national delegations, including those of China, Iran and Finland. This affords them privileged access with limited scrutiny.

Several companies stand out as being especially well represented at the talks. Dow has cumulatively sent at least 21 company delegates across all negotiation rounds, ExxonMobil has sent 14, BASF 13, Chevron Phillips 7, SABIC 6, Shell 5, and INEOS 4., Many of these firms are also among the world’s top producers of single-use virgin plastic, with Dow and ExxonMobil ranked in the top three globally. Those with the most to lose from meaningful regulation are working hardest to obstruct it.

Crucially, influence by these companies’ goes far beyond their direct representatives. Powerful trade associations – including the American Chemistry Council (ACC), Plastics Europe, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) and the European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic) – also lobby on their behalf. These ‘front groups’ push industry-friendly positions while shielding corporate members from scrutiny.

The extent and impact of informal lobbying is also deeply concerning. Civil society observers report that many delegates arrive days before the formal talks begin to host private dinners, receptions and one-on-one meetings that influence relationships and narratives. These tactics echo those used in climate talks, where behind-the-scenes lobbying often shapes outcomes before negotiations even start.

The sheer scale of the fossil fuel lobby’s presence, and their level of access to delegates, both formal and informal, highlights the structural imbalance in the negotiations. While pollution-affected communities and independent experts struggle to be heard, polluters are not only at the table – they’re dominating the room.

Betting on more plastic: case studies in expansion

While lobbying to weaken the Global Plastics Treaty, major fossil fuel companies have been expanding their plastic production infrastructure – betting against regulation and locking in future plastic pollution.

ExxonMobil

ExxonMobil has significantly increased its plastics footprint in recent years. In December 2022, the company doubled polypropylene capacity at its Baton Rouge plant in Louisiana, enabling it to produce 450,000 tonnes per year. It is now advancing plans for its Coastal Plain Project in Calhoun County, Texas – a massive steam cracker that would convert fracked gas from the Permian Basin, into up to 2.7 million tonnes of polyethylene annually, primarily for export to Asia. In addition, Exxon’s new petrochemical complex in China, expected to open this year, will be capable of producing at least 2.5 million tonnes of polyethylene and polypropylene. These expansions underscore ExxonMobil’s long-term commitment to virgin plastic growth.

INEOS

Greenpeace UK’s analysis shows that INEOS, the UK’s biggest plastic producer, has increased plastic production capacity by over a fifth since the start of the treaty talks, including major expansions in Belgium, backed by the UK government., Its €4 billion Project ONE ethane cracker in Antwerp will be the largest in Europe.,

INEOS exerts a strong influence through multiple trade associations such as Plastics Europe. Publicly, INEOS has echoed the lobbying positions of Plastics Europe, explicitly cautioning against production caps, and advocating an approach centred on recycling. This would delay meaningful regulation while allowing continued production expansion.

Shell

While Shell promotes circularity in its public messaging, it continues to invest heavily in virgin plastic production. Shell’s Pennsylvania petrochemical complex became operational in November 2022 – the same month the treaty process began – adding over 1.6 million tonnes of polyethylene capacity per year. This more than doubled its global polyethylene capacity to around 2.3 million tonnes in 2024.

It is clear from these examples that fossil fuel companies are not standing on the sidelines. They are actively building the infrastructure to produce more plastic for decades to come – while lobbying to delay, dilute or derail the treaty designed to stop it.

Profiting from pollution

Lobbying to weaken the treaty is not a trivial project. With global oil demand flattening, plastics represent a significant growth area for fossil fuel companies.

For example:

- Since talks began, Dow has earned an estimated $5.1 billion from plastics – while sending at least 21 lobbyists to the treaty negotiations.

- Shell earned $326 million from the manufacture of plastics in 2023 and a further $956 million in 2024.

- ExxonMobil has earned a combined $5.3 billion from its chemical products division since talks began – which includes materials used for plastic production such as polyethylene and polypropylene.

These profits highlight the fundamental conflict of interest at the heart of treaty negotiations. Companies are expanding plastic production while lobbying against regulation because a strong treaty threatens their core business model and long-term profits.

Since talks began, Dow earned an estimated $5.1 billion from plastics while sending at least 21 lobbyists to the treaty negotiations.

The machinery of influence

The Global Plastics Treaty negotiations have become a theatre of corporate influence. Petrochemical and fossil fuel companies, fearing limits on plastic production, have mobilised a sophisticated lobbying effort – not only around the negotiating rooms, but inside them.

Different treaty, same tactics

The obstruction on display at the plastics treaty mirrors the industry’s behaviour in climate talks. According to the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), fossil fuel and petrochemical companies are using the same playbook:

- Delay: Dragging out timelines.

- Distract: Focusing on waste and recycling instead of cutting production.

- Discredit: Undermining scientific consensus and civil society voices.

- Dominate: Sending large delegations and dominating the room.

“These strategies are lifted straight from the climate negotiations playbook.”

– Delphine Lévi Alvarès, CIEL

This is part of a broader effort by polluters to position themselves as partners in solving the crisis while blocking the very measures needed to address it. Common tactics include: promoting chemical recycling, despite evidence that it is polluting and not commercially viable at scale; funding token clean-up projects to distract from rising production; and pushing circular economy narratives, using vague promises of recycling and reuse to justify continued expansion of production.

One of the clearest examples of this distraction strategy is the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW). In 2024, a Greenpeace Unearthed investigation exposed the greenwashing practices of the Alliance, whose founding members include Shell, ExxonMobil, Dow and TotalEnergies. While the AEPW promoted clean-up projects in the Global South, just five of its members were simultaneously producing over 1,000 times more plastic than they claimed to recover over a five-year period. The investigation further revealed that the AEPW was specifically created to shift global policy debates away from binding plastic reduction measures and towards waste management approaches favoured by industry.

Industry actors also work behind the scenes to shape domestic policy environments. In the 2022 US election cycle, petrochemical companies and plastics industry trade associations known to lobby the plastics treaty collectively spent nearly $60 million on campaign contributions and congressional lobbying – seeking to block strong global rules before they are even written.

Industry efforts to shape the treaty extend well beyond formal lobbying. Reports of intimidation and interference have emerged, including allegations of industry representatives targeting independent scientists, and pressuring national delegations to replace technical experts with industry-friendly figures.

This is not just a problem of individual bad actors: it is structural. The UN still lacks a binding, enforceable conflict of interest policy for multilateral environmental negotiations. As a result, critical treaty spaces – from climate to chemicals to biodiversity – remain wide open to corporate capture.

Conflict of interest blocks progress on plastics

There is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations: the same fossil fuel and petrochemical companies that profit from plastic pollution are being allowed to shape the treaty designed to end it. This is not just inappropriate – it is a textbook case of conflict of interest.

Powerful polluters are drowning out other voices

Companies including ExxonMobil, Shell and INEOS are expanding virgin plastic production while lobbying against caps and promoting false solutions like chemical recycling. Their participation in the treaty process is not neutral engagement; it is a strategic effort to protect profits and delay regulation. This creates an inherent imbalance, where polluters are given a platform while the communities most affected by plastic pollution struggle to be heard.

Industry actors are ‘putting their fossil-fueled profits above human health’ – a dynamic that undermines both the treaty’s legitimacy and its ability to deliver meaningful outcomes. Unless rules are put in place, the Global Plastics Treaty risks becoming the latest agreement written by those it is meant to regulate.

The draft treaty text clearly reflects industry influence, with explicit references to private sector involvement in key areas. This could entrench corporate influence in the treaty’s structure by giving polluters a formal role in implementation, oversight and financing.

Trust in the process is eroding. Civil society groups, frontline communities and even some government negotiators have voiced concern that fossil fuel lobbyists are obstructing progress, distorting science and silencing less powerful voices.,,,

Without enforceable safeguards, the treaty risks becoming an instrument of delay rather than a vehicle for real change.

It’s time to kick polluters out of plastics treaty negotiations

“There is a fundamental and irreconcilable conflict between the interests of the plastics industry […] and the human rights and policy interests of people affected by the plastics crisis.”

– The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

A treaty to reduce plastic pollution cannot be shaped by those profiting from plastic expansion.

Unless decisive action is taken, the Global Plastics Treaty will remain vulnerable to corporate capture. The time to act is now.

Greenpeace recommendations

To protect the integrity of the Global Plastics Treaty and ensure real change, Greenpeace calls on the UN and the INC Secretariat to:

1. Ban fossil fuel and petrochemical lobbyists from plastics treaty negotiations and future Conferences of the Parties

The companies profiting from plastic pollution must not be allowed to shape the treaty meant to stop it. The UN should adopt clear rules excluding all fossil fuel and chemical industry actors – whether they are formal observers, industry representatives within national delegations or unofficial lobbyists – from all plastics treaty spaces.

There is a clear precedent for action to prevent conflicts of interest. The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control explicitly excludes tobacco industry representatives from policymaking, recognising that their profit motive is incompatible with public health objectives.

2. Embed a strong conflict of interest policy in the treaty

The treaty must include binding safeguards against undue influence. This should follow the model of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and apply across all plastics treaty bodies.

As an immediate priority, the UN must:

- Recognise the need to avoid influence from vested interests in the treaty’s preamble.

- Delete from the treaty text any references that could embed the influence of the private sector in the treaty’s implementation.

- Urgently establish a conflict of interest policy for any scientific subsidiary body of the treaty that is set up to identify which chemicals and products to regulate.

3. Ensure meaningful public and scientific participation

The treaty must prioritise those most affected by the plastics crisis. The UN should guarantee space for independent scientists, Indigenous Peoples, frontline communities, waste pickers and public interest civil society groups to shape negotiations and the implementation of the treaty.

If the goal is to end plastic pollution, the rules cannot be written by those who profit from it.

Appendices

Greenpeace’s analysis is based on estimated global production figures for polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) for November/December 2022, 2023 and 2024 financial years, for Dow, ExxonMobil, BASF, Chevron, Shell, SABIC and INEOS, produced by Market Research Future.

Market Research Future’s own production estimates are based on information disclosed in corporate reporting – such as annual reports, investor presentations and press releases – supplemented by information obtained from third-party industry platforms, including Polymerupdate, Argus, Intratec and Plastics World, which can include plant-level data. Market Research Future also relies on well-placed industry sources. Market Research Future’s production figure modelling also takes into account selling prices, plant capacities, utilisation rates and supply and demand data.

To calculate an equivalent in rubbish trucks, we have used a standard UK refuse truck which carries approximately 12 metric tonnes of plastic waste. This figure is based on the typical load capacity of the Dennis Eagle Elite 6, a widely used UK waste collection vehicle with a gross weight capacity of up to 26,000 kg.

Calculation:

Total plastic produced (75,447,000 tonnes) ÷ 12 = 6,287,250 estimated number of rubbish trucks.

Rounded to the nearest hundred thousand = 6.3 million.

This estimate covers two of the world’s most widely-used polymers, commonly found in packaging and consumer goods. It excludes other major plastic types such as PET and polystyrene, and excludes 2025 production data even as treaty talks continue into this year. As such, the final figure is an underestimate of total plastic production during this time.

Greenpeace UK analysis is based on Market Research Future data covering Dow, ExxonMobil, BASF, Chevron, Shell, SABIC and INEOS – seven of the top treaty lobbyists.

The estimate reflects confirmed increases in polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) capacity between 2022 and 2024, totalling approximately 1.4 million tonnes.

Note: This is likely an underestimate. It excludes projects built since 2024, other plastic types (e.g. PET) and unconfirmed expansions.

This estimate is based on reported global capacities for polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene from INEOS’ annual reports for 2022–2024.

Polyethylene capacity rose from 3,538 kilo tonnes per annum (kta) in 2022 to 4,238 kta in 2024.

Polypropylene capacity rose from 1,798 kta in 2022 to 2,251 kta in 2024.

Combined, this represents a 21.61% increase in plastics-related production capacity.

Major drivers include expansions at US sites (Battleground, Cedar Bayou, Chocolate Bayou), the 2024 acquisition of the Lavéra site in France, and the Tianjin Nangang Ethylene Project in China.

Dow’s estimated $5.1 billion in plastics-related profit since November 2022 is based on the company’s reported Operating EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) from its Packaging & Specialty Plastics segment.

In 2023, Dow reported $2.7 billion in Operating EBIT for this segment.

In 2024, the reported figure was $2.373 billion.

Together, these amount to $5.073 billion, rounded to approximately $5.1 billion.

The Packaging & Specialty Plastics segment includes core plastic products such as polyethylene, HDPE, LDPE, LLDPE and polyolefin plastomers, making it a reasonable proxy for Dow’s plastics profits.

Note: This calculation relies on full-year financial data for 2023 and 2024 due to the lack of publicly available quarterly breakdo