- Report

Power Shift: how the Labour government can bring down bills and bolster net zero by curtailing the power of gas

Overview

This report proposes a route to lower electricity prices across the UK by £5.2 billion per year by 2028. Currently gas is responsible for much of the UK’s sky-high electricity bill, but the government has the opportunity to limit their power and unlock lower bills.

The UK’s electricity market links prices to volatile gas costs, driving an affordability crisis. Households and businesses pay far more than necessary, despite renewables now being the cheapest energy source.

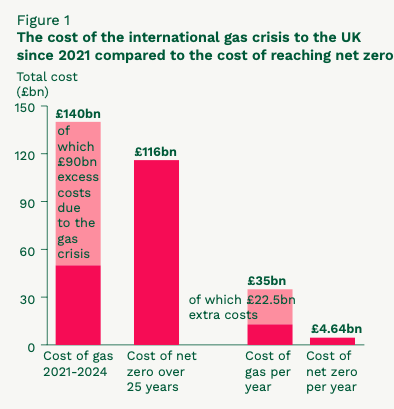

This flawed system has cost the UK economy billions. Since 2021, £90 billion extra has been spent on gas, with £40 billion in public money used to cushion soaring household bills.

We propose moving gas plants into a Regulated Asset Base (RAB). This would make gas a strategic reserve with stable, regulated returns, reducing its impact on market prices.

The RAB model could be rolled out within two years and deliver fast, wide-reaching savings. By 2028, it would cut bills by £5.1 billion annually – including £65 for the average household and £3.3 billion across businesses.

This is a low-cost, high-impact reform with broad benefits. It would support vulnerable households, cut costs for industry, and accelerate the shift to clean, secure energy.

JUMP TO SECTION

Executive summary

The UK is facing an enduring energy affordability crisis that affects millions of households, undermines industrial competitiveness and slows progress on climate goals. Even though renewables are now the cheapest form of electricity generation, UK consumers and businesses continue to pay inflated electricity prices that are pegged to the extremely high and volatile price of gas.

The unaffordable gas-driven pricing of our electricity market has caused a cost of living crisis, forced the closure of many businesses and industries, and damaged our economy. Since 2021, our overreliance on gas and its volatile prices has forced the government to make £40 billion in emergency payments to help households cope with their soaring bills, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent prices soaring. These inflated prices have resulted in the UK spending £90 billion more on gas than if prices had stayed the same, equivalent to £1,300 per person.

Now the Labour government has a unique opportunity to deliver an energy system that is fit for the future: providing energy security by ending reliance on fossil fuels, and unlocking cheaper renewable electricity for consumers and businesses by taking gas power out of the electricity market.

This new research by Greenpeace UK and Stonehaven outlines our recommendation to stop gas setting the price we pay for electricity and control the negative impacts of gas in the electricity market. Our recommendation is to bring gas plants into a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) system, administered by the National Energy Systems Operator (NESO). In this model, gas plants would provide a strategic reserve of energy, at an agreed price, when this is needed to meet electricity demand. This would ensure that gas plants get regular, stable returns, while keeping energy costs for the rest of the economy stable and noticeably lower.

This policy could be delivered – and start producing meaningful savings – in the next two years. Our analysis shows that it would result in annual bill savings across households and the economy of £5.1 billion in total in 2028. This represents a saving of £65 a year to the average household and £3.3 billion across all businesses and industry. Rapidly implementing our recommendation would contribute a significant amount towards the government’s vital pledge to lower household energy bills by £300 a year. Additional bills savings can be made via a range of alternative interventions, including moving policy levies into general taxation, extending the Contracts for Difference scheme to 25 years and improving energy efficiency, as outlined by E3G’s Clean Power Mission report.

As this paper shows, this is not just an energy policy – it is a social, economic and climate policy in one, enabling this Labour government to simultaneously lower bills, support vulnerable households, strengthen British industry and accelerate the clean energy transition.

Why we propose a Regulated Asset Base (RAB)

Our RAB model proposes bringing gas plants into a strategic reserve by creating an asset that represents the economic value of gas plants, and giving plant owners a licence that gives them the right to recover that value plus operating expenditures from bill payers. The level of these costs are agreed by the regulator and updated on a regular cycle. This would prevent gas plants from extracting scarcity rents and would lower electricity bills across the economy.

The RAB would be implemented via a change to the generation licence conditions that apply to participating gas plants, which would be undertaken by Ofgem. This would restrict the ability of participating gas plants to trade independently of instruction by NESO.

Most gas plant owners are facing considerable uncertainty about the future, so having a defined path to revenue – which a RAB would represent – could be a very attractive option. We expect that many gas plants will join the reserve on a voluntary basis, and there are further mechanisms to encourage others to join.

The benefits of this model are the relative ease and low cost of implementing it compared to other options.

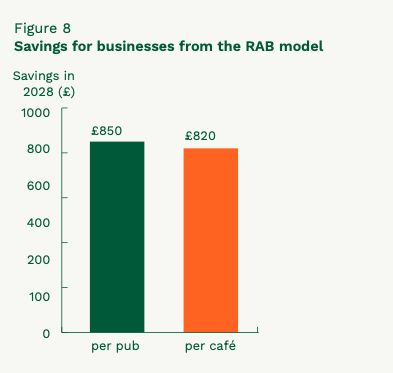

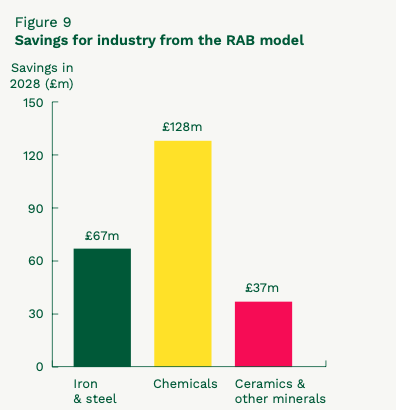

The headline saving of this model is a peak net saving of £5.2 billion for all electricity consumers in 2030. We estimate that the RAB would save the average household £65 per year as soon as 2028, which is equal to £1.7 billion in total. Pubs would save £38 million and cafés would save £9 million in 2028. This is the equivalent of £850 for an average pub and £820 for an average café. Finally, in 2028 we estimate the RAB to save the iron and steel industry £67 million, the chemicals industry £128 million, and ceramics and other minerals (e.g. glass and cement) £37 million.

Foreword by Melanie Onn MP

Melanie Onn is the MP for Great Grimsby and Cleethorpes, having served from 2015-2019 and been re-elected in 2024. A former Deputy Chief Executive of RenewableUK and regional union organiser, she has held multiple shadow ministerial roles and now sits on the Energy Security and Net Zero Committee.

Renewable energy is better for our planet, better for our economy, and better for people’s pockets. Across the UK, we are generating more clean, affordable renewable electricity than ever before. Yet millions of households and businesses are still being hit by high energy bills because gas power stations continue to set the price of electricity, despite cheaper renewables providing 40% of our electricity needs.

This is a legacy of a broken energy market, where global gas prices, driven up by events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, dictate costs here at home. The result is inflated energy bills, even when renewable energy is supplying the UK with green, cheap and homegrown power.

In my constituency of Great Grimsby and Cleethorpes, and in communities across the UK, I’ve seen the urgent need to tackle the cost of living crisis. If we can fix the outdated way electricity prices are set and curb the power of gas to dictate prices, we can lower bills for households, businesses and industry. Cheaper energy for industry also means lower costs for the goods and services we all rely on, easing pressure on families who are struggling to afford the basics let alone the luxuries.

We also have a major opportunity to deliver long-term prosperity through the net zero economy, which is growing three times faster than the overall economy. Across the UK, it already supports over 270,000 good-quality jobs, including hundreds in and around Great Grimsby and Cleethorpes, and has the potential to create many thousands more. By unlocking lower bills and continuing to invest in clean energy, we can ensure those jobs are not just protected, but expanded, up and down the country.

This important report from Greenpeace UK and Stonehaven offers the Labour government a practical, forward-looking policy solution – one that can lower bills, strengthen energy security and deliver on our promise to improve people’s lives.

The UK’s sky-high electricity bills are being driven by the cost of gas. Our energy prices are higher than those of many of our closest neighbours because of the system used to determine electricity prices, and our reliance on gas power generators.

The massive hike in the price of gas since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has hit UK households and businesses hard. Gas prices grew exponentially because many countries chose to reduce or stop importing Russian gas. When the supply of Russian gas fell, it inflated the global commodity price. So even though only 4% of the UK’s demand for gas was met by Russian imports, prices rocketed because around 50% of our gas needs are met by imports, and domestic production is also sold on the open international market.² Unregulated dependence on the fossil fuel industry binds us to a volatile and unstable international market, where any dictator or international crisis has the potential to destabilise our entire economy. We urgently need to end this dependence, and the quickest and cheapest way to do so is by scaling up renewable energy.

Between summer 2021 and early 2023, the energy price cap almost quadrupled, from £1,084/year to £4,059/year. While costs have fallen from their peak, the price cap is still 59% higher than it was before the crisis.³ The Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) has estimated that since 2021 the UK has spent £90 billion more on gas than if prices had stayed the same. Spread equally across the population, this is equivalent to £1,300 per person.4

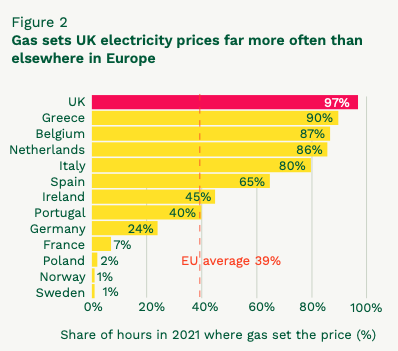

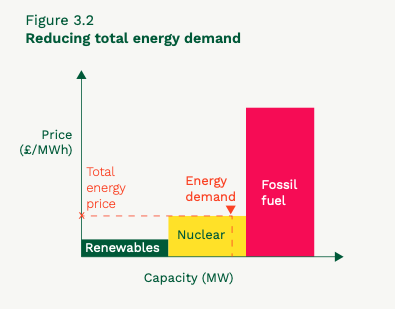

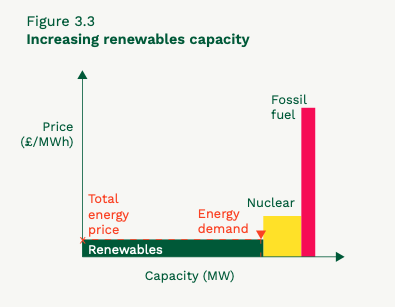

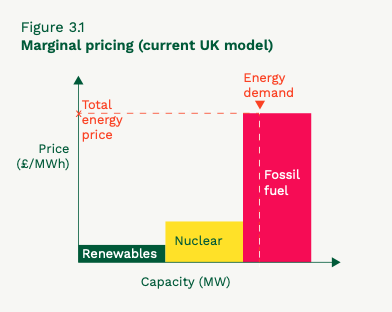

Under the UK’s ‘marginal pricing’ system, the price of electricity is set by the most expensive source of energy needed to meet demand at any given time.⁵ In practice, this means that even a small reliance on gas-powered plants during peak times, when other sources have reached capacity, results in the entire market paying the high cost associated with gas-fired electricity generation. This is regardless of the much lower prices associated with renewable electricity.

This system gives gas-fired electricity generators unique power to dictate the price of electricity in the UK. Despite accounting for only 39% of total electricity generation in 2021, gas-fired power plants were able to set the wholesale price of electricity 97% of the time.⁶ By contrast, gas sets the price 24% of the time in Germany and only 7% in France, with the EU average at about 39%.⁷ Consequently, despite the Labour government’s focus on rapid delivery of new renewable energy projects, UK electricity bills for homes, businesses and industry are significantly higher than they should and could be.

How gas dictates the market price

Gas-powered electricity generators currently play an important role in our energy system because they can rapidly dispatch energy when electricity demand exceeds the available supply from renewables. This balancing function is necessary while more effective long-duration storage is developed to even out the peaks and troughs of renewable generation. However, this doesn’t mean gas should set the price for all of the wholesale electricity the UK consumes. The fact that gas currently dictates the market price is a costly glitch in our energy market system.

Until gas is phased out of our energy system, gas plants have disproportionate power in the market. When power from gas generators is required to meet energy consumption needs, they can demand massive ‘balancing payments’ to supply the country with the additional power. For example, on 8 January 2025, Connah’s Quay and Rye House gas plants received over £12 million to supply just three hours of electricity, which was 50 times the market price.⁸

The Labour government is working to address this imbalance by investing in renewable energy delivery through GB Energy, de-risking the market and crowding in significant private investment, and by bringing more new renewable projects into its ‘Contracts for Difference’ scheme. This scheme allows renewable energy generators to receive a fixed price for the electricity they produce, which means an ever-increasing number of renewable energy projects are no longer pegged to the volatile gas-driven market price. This is central to the government’s Clean Power 2030 mission and will make a significant impact on consumer energy bills.

However, while these reforms are promising they are unlikely to result in significant bill reductions before 2030. In the meantime, without a fundamental market redesign that addresses how electricity prices are set, pressures are likely to persist, and consumers and businesses will continue to face disproportionately high costs.

For the planet and our pockets we need to phase out our dependency on gas, while protecting and including workers. While we remain bound to a pricing system designed for a previous era, households and the economy are paying a heavy price. This report outlines a solution to this problem that will reduce bills, address this distorting market power, and give the government control over the process of removing gas from the system as the role of fossil fuels diminishes. First, we set out the many benefits of doing so.

The inflated price UK consumers pay for gas can also be understood by looking in more detail at how costs pass through the energy system. Energy suppliers’ job is to ensure that there is enough electricity available every half hour to meet consumers’ needs. This means they need to buy power from a mix of generators.

Suppliers buy power from electricity generators through a combination of longer-term contracts and short-term trades. Renewable generators produce an amount of power that can be predicted over the course of the year, even if their day-to-day output is less predictable than that of gas generators (due to daily and seasonal fluctuations in wind and sunshine). They tend to sell this average annual volume via long-term contracts, as their lack of predictable output means there is less value in short-term trading. These contracts will typically be pegged to the wholesale price, either directly or through further trading in that power by the energy supplier or an energy trader.

There is no single wholesale price, as electricity can be bought and sold in contracts of multiple duration in a variety of exchanges, but pegging in this sense normally means the price of power on the day-ahead market in an exchange.

Renewable generators with a Contract for Difference – a CfD – enjoy a guaranteed ‘strike price’. This means that generators are paid a specific price per megawatt-hour (MWh) regardless of the wholesale price at the time. When the wholesale price is lower than the strike price, suppliers make this up to the generator, and when it is higher the renewable generator pays back the difference.

Unlike renewable generators, gas plants typically seek to sell their power in response to signals in the day-ahead or shorter-term markets. This is because they are better able to respond to such signals: they can quickly adjust the amount of electricity they supply in response to fluctuations in demand, and are not weather-dependent. When energy suppliers have exhausted the power from their long-term contracts, they buy power in short-term markets to make up any shortfall. The amount gas plants can charge for this power partly depends on how many gas plants are online and the efficiency of these plants, and partly on demand from suppliers. Suppliers also have the option of paying one of their larger customers – such as an industrial consumer – to turn down demand, but the cost of doing so is typically extremely high.

When suppliers have no other option, they have to pay huge sums to get power from gas. And as the number of gas plants has declined alongside the removal of heavily polluting coal plants from the system, suppliers have fewer options to meet demand, which has increasingly inflated prices. Gas plants also get revenues from the balancing market, which is for very short-term (less than one hour) responses. Over the past five years, the average balancing price for power from gas has been around £250/MWh. Over the same period, average day-ahead electricity prices, which have overwhelmingly been set by gas power, have been £115/MWh. This figure is calculated using Ofgem's monthly average for day ahead baseload contracts, averaged over a five-year period from June 2020 to June 2025. By contrast, the CfD strike prices in 2024 were £102/MWh for offshore wind, £89/MWh for onshore wind and £50/MWh for solar.⁹

This difference is essentially due to gas plants charging what they can because the resource they represent is scarce. This is rent-seeking behaviour by gas plants that directly damages the finances of families, businesses and industry nationwide.

Affordable electricity is essential to modern life. It powers homes, sustains public services and underpins industrial production. Yet today, millions of people across the UK struggle to afford enough energy to meet their basic needs, while businesses see the cost of energy eat into profits and put jobs at risk. The energy bills crisis has significant implications for public health, economic competitiveness, political stability and climate policy.

Our energy system must be fit for a new global reality – one that recognises that gas is not only bad for the planet, but also bad for households, businesses and energy security. By restructuring the market to allow cheaper renewable energy to reduce costs for billpayers, the government can deliver on its targets on climate, clean power and economic growth at the same time as tackling poverty and inequality.

Social benefits

High energy bills have driven the cost of living crisis, which is still one of the most pressing issues in the UK. Over six million people are currently living in fuel poverty.¹⁰ Cold homes contribute to poor health outcomes, particularly among vulnerable groups including older adults, children, pregnant people and those with chronic health conditions.¹¹

Each year there are approximately 35,000 excess winter deaths in England and Wales, many of which are linked to cold homes.¹² This is a clear public health failure and puts a huge strain on NHS services. Research suggests that the NHS could save hundreds of millions of pounds each year if people living in fuel poverty had warmer homes.¹³ Alongside energy efficiency measures to reduce overall energy consumption and wastage, the government must bring down energy prices.

Improving energy affordability would yield broader economic benefits. Households with lower energy bills have greater disposable income, which can be invested in local economies and improve overall quality of life. Research has found that boosting low incomes is a key route to levelling up areas of the UK that feel left behind.¹⁴ Reducing energy costs will have an outsized benefit for people on lower incomes, therefore working as an effective anti-poverty measure.

Economic benefits

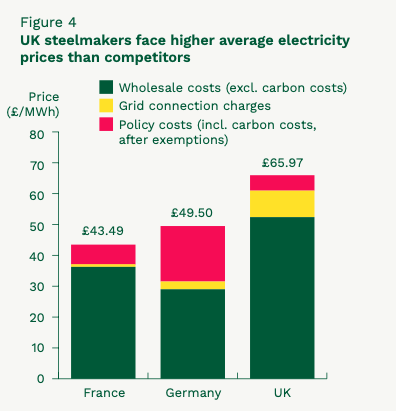

Small businesses, as well as large industrial sectors such as manufacturing and steel, are buckling under sky-high energy costs that reduce competitiveness and threaten jobs. The UK has the highest industrial electricity prices of any International Energy Association (IEA) member country.¹⁵ The impact of high industrial electricity prices is exemplified by the UK steel industry’s competitiveness issues, which rightly receive significant public and political attention. According to UK Steel, the average electricity price faced by UK steelmakers for 2024-25 is £66/MWh, compared to £50/MWh in Germany and £43/MWh in France.¹⁶ As a result of this disparity, the UK’s steel industry had to pay £37-50 million more than those of Germany and France in 2024-25. This is a structural disadvantage that undermines the viability of a range of energy-intensive industries and the livelihoods of thousands of workers.

As we transition to a modern energy system powered by renewables, demand for electricity will increase. The government must act fast to fix the price-setting problem in the energy market to ensure that the UK can compete for international investment in future energy-intensive industries.

While government interventions – such as support for British Steel¹⁷ and changes to industry levies¹⁸ outlined in its Industrial Strategy – have provided or plan to provide targeted support, these are reactive, small-scale measures that do not address the root cause of high prices. By contrast, our proposal would address the impact of high gas prices on electricity markets, delivering lower prices for all.

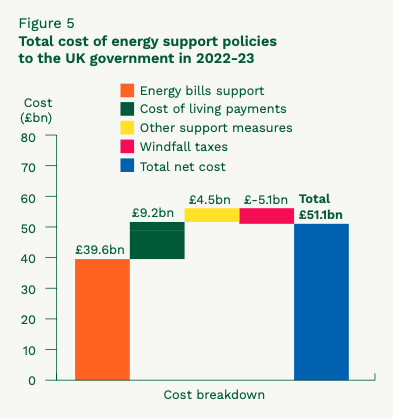

UK gas prices began to rise in 2021, as the global economy recovered from the pandemic but gas production capacity had yet to come back online. In early 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. European governments responded by refusing to buy Russian gas, pushing prices up further. During the peak of the crisis, the UK government spent over £40 billion on emergency payments to shield households from soaring energy bills; the total net cost of energy support was £51.1 billion (2% of GDP), even when offset by higher windfall taxes through the Energy Profits Levy and Electricity Generator Levy.¹⁹ While necessary in the short term, this level of public expenditure is clearly not sustainable. Reforming the electricity market to prevent gas from setting the marginal price could help prevent similar crises in the future.

Political benefits

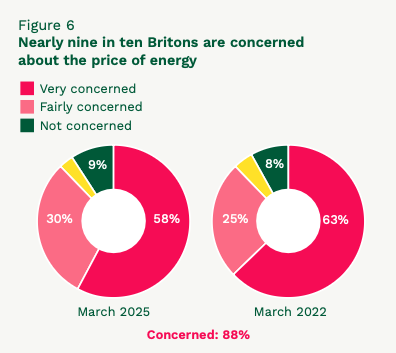

Energy affordability has been a major political issue for the last few years. In a recent survey, 88% of Britons, cutting across demographic and political lines, said they are concerned about the current cost of energy.²⁰ Public demonstrations on the importance of government schemes, such as the Warm Homes Discount and winter fuel payments, are evidence that the government must either tackle affordability or continue to provide financial support for inflated energy prices.

Labour pledged to lower household bills by £300 a year before it came into power. Now in government, it must focus on delivering that goal.

Misinformation campaigns have sought to link net zero policies to rising energy costs. This government can expose and undermine these misleading narratives by demonstrating that fossil fuel volatility is the problem. Cutting gas plants’ price-setting power in the market would lower costs and build public trust in the broader climate and energy transition agenda.

In the face of increasing global instability, it is imperative that the Labour government focuses on delivering energy independence. Homegrown clean renewable energy is the only route to achieve this. A UK energy system that doesn’t break from fossil fuels will leave us beholden to volatile international markets and susceptible to price shocks and market manipulations.

Climate benefits

Reforming how our energy system operates is also essential for achieving the UK’s climate goals. Gas-fired electricity generators are currently responsible for approximately 8% of the UK’s annual carbon emissions,²¹ with some individual sites like Pembroke gas plant among the largest single emitters in the country.²² Limiting the role of gas power generation is therefore a key step towards the UK’s climate targets.

Gas generation is also inefficient – it converts only about 53% of fuel energy into electricity.²³ The Climate Change Committee notes that over 50% of energy used in the economy is wasted through the inefficiency of fossil fuels, highlighting that electrification could halve that waste.²⁴ By contrast, renewables avoid fuel costs entirely and deliver significantly higher system efficiency.

The Climate Change Committee also advises that 60% of emissions reductions must come from electrification across homes, transport and industry.²⁵ It has recommended that the government prioritises making electricity cheaper, in order to deliver on its legally binding climate targets.²⁶ Gas plants’ role in making electricity expensive is slowing the transition, as consumers do not see a cost advantage to making the switch to electric heating systems and vehicles.

When the financial benefits of renewables are realised, the move away from fossil fuels can happen at pace. A reformed market would support faster electrification, reduce emissions and build public confidence in the clean energy transition.

The core purpose of taking gas plants out of the power market is to prevent them extracting scarcity rents and thus inflating energy bills. Doing so would mean that gas plants couldn’t sell their power in the open market but could only switch on when the system required them to.

Our recommended option is a strategic reserve in which participating gas plants are operated by NESO and recover their costs via a Regulated Asset Base (RAB). We believe that with sufficient government focus, this could be delivered within two years.

How our RAB proposal works

Our proposal is that gas plants are owned by a company that operates much like a standard utility, i.e. a company that makes consistent but low returns. This would reduce the cost of capital associated with their operation. This utility may be wholly new, or – pending changes to legislation which prevent ownership of gas plants – may be an existing regulated energy company, such as a gas or electricity network.

Whoever owns the plants needs to be paid to make sure NESO can use their output. We assume that any payment would need to cover the costs of operating the plants as well as recovering the cost of capital. Payment for gas would be handled by NESO as a monopsony buyer of power generated. We assume that capital and fixed operational costs are £872 million/year, and fuel costs are £4.2 billion/year.

We recommend that we utilise an existing mechanism for providing assurance around cost efficiency: a Regulated Asset Base. This option involves creating an asset that represents the book value (the value of a company’s assets minus its liabilities) of plants, and giving plant owners a licence that gives them the right to recover the depreciation of that value, plus operating expenditures, from billpayers. The level of these costs are agreed by the regulator and updated on a regular cycle.

Given that the outputs required from gas plants over the year are fixed and known in advance, we recommend structuring the amount that plants are allowed to recover from consumers to be in line with the RPI-X model originally used at privatisation, rather than the more complex RIIO model currently used by Ofgem. Under this model, ‘X’ is what the regulator believes gas plants can reduce their real costs by each year, and can be set on a nominal basis rather than requiring specialist knowledge. Gas generators’ revenues and profits would be capped, avoiding price spikes and profiteering, and providing greater consumer protection while also ensuring predictable returns. This model would suit gas plants better than RIIO during the period when they are being phased out and are required to run less and less frequently.

The model has three components: designing the RAB, granting powers for NESO to operate the plants and buy gas, and getting gas plants into the strategic reserve.

Designing the RAB

The UK government has implemented two separate RABs for two major projects within the last decade – Sizewell C and the Thames Tideway Tunnel. These RABs were tailored to the projects’ particular needs, with the Sizewell C RAB structured to provide revenue during construction to encourage financing of the riskiest phase of the work, and the Thames Tideway designed as a bespoke independent project recovered via Thames Water’s customers. Sizewell C required bespoke legislation, while the Thames Tideway Tunnel utilised existing secondary legislation that permitted Ofwat to endow a company with a special licence.

The design of a RAB for the strategic reserve should be much simpler than for either of these projects. It needs to allow the recovery of any remaining capital costs of participating gas plants over a given number of years, as well as their operating expenditure. This cost can be placed into network charges or recovered from the cost that NESO charges suppliers to balance the power system – either would function well. Our analysis indicates that this cost is likely to be £17.4 billion in total, or £11 on the average household bill per year. This compares favourably with the £30/year household cost of the Capacity Market, which overwhelmingly supports gas and which this proposal would in large part replace.

The RAB should only allow additional capital investments that require strategically necessary refurbishment, to avoid promoting and locking in this polluting infrastructure.

The RAB should be implemented via a change to the generation licence conditions that apply to participating gas plants, which would be undertaken by Ofgem. This would restrict the ability of participating gas plants to trade independently of instruction by NESO.

Powers for NESO

Given Ofgem’s independent status, the government could pass primary legislation to ensure Ofgem feels confident that it has the powers to make such modifications to generators’ licences. This legislation would also allow network utilities to own gas plants, in case existing owners choose to sell up.

The government could also choose to clarify the provisions in the Energy Act 2023 that confer on NESO the functions of coordinating and directing the flow of electricity over the transmission system. This would give NESO the ability to operate the plants for the purposes of system security, but is not integral to the RAB model. NESO would then need to specify, through guidance to the market, how and when it would use the gas plants for the purpose of system security.

Getting gas into the strategic reserve

Moving gas plants into this reserve can be accomplished using either the carrot or the stick.

Most gas plant owners are currently staring down the barrel of an ever-decreasing market share, and there is very little information from the government about how it expects them to cover their costs in the future. In the face of such uncertainty, having a defined path to revenue – which a RAB would represent – could be very attractive. As such, we expect that an invitation to gas plants to join the reserve on a voluntary basis would have significant take-up. Owners could sell up to an existing utility seeking to participate in the scheme or establish their own.

At the same time, there will be gas plant operators with older plants who no longer have to pay down financing costs and who are confident about their ability to maximise revenue in the market. Convincing these operators to join the reserve will require mechanisms that forcibly restrict their forward revenue, particularly given the exit of their competition from the market.

The necessary mechanisms already exist within primary legislation. Closing the Capacity Market to gas would deprive gas plants of a guaranteed revenue stream, and can be achieved through changes to eligibility requirements. Applying an ever-tightening Emissions Performance Standard to gas plants that choose to stay outside the RAB will prevent them from generating beyond a certain number of hours in the year.

Other options for ownership of gas plants

We recommend creating a new utility to manage gas plants, as set out above. Alternative options for gas plant ownership include nationalisation or leaving them in current ownership, which we discuss below.

Nationalisation

Nationalisation of gas plants has been proposed by the not-for-profit organisation Common Wealth.

The cost of purchasing these plants is very high. Our recommended RAB model assumes that the purchase price of all of these plants would be their depreciated value, which we estimate as £17.4 billion, plus the Net Present Value of their forward revenue (£50 billion), which comes to about £67.6 billion in total. As a point of comparison, the total capital spending limit of the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) over the period 2023–2030 was laid out in the 2025 Spending Review as £56.7 billion, not including Sizewell C. While there are measures the government could take to reduce the upfront cost of this move – depending on its appetite for spooking capital markets – we regard this cost as likely being beyond the government’s fiscal envelope.

Current (private) ownership

Leaving plants with their existing owners in the short term is probably the least disruptive option, but the very different operational model we propose is likely to reduce owners’ appetite to retain the assets. Equity-heavy plant owners with an emphasis on short-run gains are likely to take the view that their capital may be better suited to higher-risk assets elsewhere. This is particularly the case if they have built a business around identifying short-term trading opportunities, where investment in batteries may be more attractive.

Other options for payment

We recommend payment through a Regulated Asset Base model, as outlined above. But there are other options for funding, including via the Treasury or the billpayer.

The Treasury

The government has the option to bypass the regulator and handle these payments directly, with the Treasury acting as the overseer of gas plants to ensure that costs are being incurred efficiently. This has the benefit of reducing bills to the greatest extent, but further challenges this government’s spending plans.

The billpayer, via the Capacity Market

An alternative is to leverage the existing Capacity Market (CM) mechanism to provide gas plants with a simple availability payment to cover their costs via a bespoke CM agreement. This would be recovered from bills. This option represents the easiest path to delivery, but may not be optimal in the long term. Cost control in the Capacity Market is achieved through a competitive auction, and although long-term CM agreements are available they are not intended to cover the whole lifetime of the plant. A simple inflation-linked availability payment allocated non-competitively – as it is likely it would have to be offered to all gas plants – may not necessarily represent efficient costs. The CM is not designed to achieve this outside of an auction framework. There is no mechanism to enable a capacity contract to be reopened if costs materially change. This means that the billpayer could be on the hook for higher costs, without any form of recourse, for 15 years.

A just transition for gas workers

Gas plant workers have played a critical role in maintaining the reliability of the UK’s energy system over decades. Now the government and industry have to deliver a just transition for workers, in consultation with those workers and their unions.

Under a RAB model for a strategic reserve of gas generation assets, the government would take on a greater degree of responsibility for ensuring that workers enjoy good working conditions, with commitments to job retention, retraining and workforce consultation. The process of agreeing the terms of the RAB should be drawn up in consultation with workers and their unions, and the contract offers an opportunity to secure good terms and conditions for workers employed on plants within the scheme.

As the Climate Change Committee has outlined, unabated gas generation needs to fall to below 2% of electricity supply by 2040, with a full phase-out by 2050, to meet legally binding carbon budgets.32 Ensuring a well-managed, just transition for workers in this declining industry is essential.

Delivering this transition will demand coordinated action from government, industry and trade unions, with transparent planning and targeted support where risks such as regional job losses or skills gaps emerge. Decarbonisation must go hand in hand with social responsibility – ensuring that energy workers are supported through the changes ahead.

This section provides an overview of the results of our analysis. Our approach is laid out in the Methodology section below.

On top of the cost of servicing the RAB outlined above, NESO would have to contract for the volume of gas it expects to need over the course of the year for the operation of the gas plants. We assume that NESO would be at least as efficient as existing operators at procuring gas, although a single buyer may have greater market power. In total, the operation of the strategic reserve would cost £5 billion per year, recovered from consumer bills. Net savings for all electricity consumers are estimated to be £5.1 billion in 2028, and would peak in 2030 at £5.2 billion.³³

It is worth noting that we assume gas power stations would no longer pay for UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) credits or the Carbon Price Support. This would mean that the Treasury would lose £2.1 billion in taxes in 2028, and £0.6 billion in 2035. If gas power stations were to continue paying carbon costs, the savings for electricity consumers would fall but the costs to the Treasury would be lower.

Balancing costs are forecasted to fall, as investment in the grid means NESO can move electricity across the country to where it’s needed, rather than having to pay some areas to turn up generation and others to turn it down. This means that household savings are higher in 2030 than in 2035, as are savings for cafés and pubs. However, savings for energy-intensive industries remain unchanged as they already receive compensation for the carbon costs on their electricity use.

Savings for households

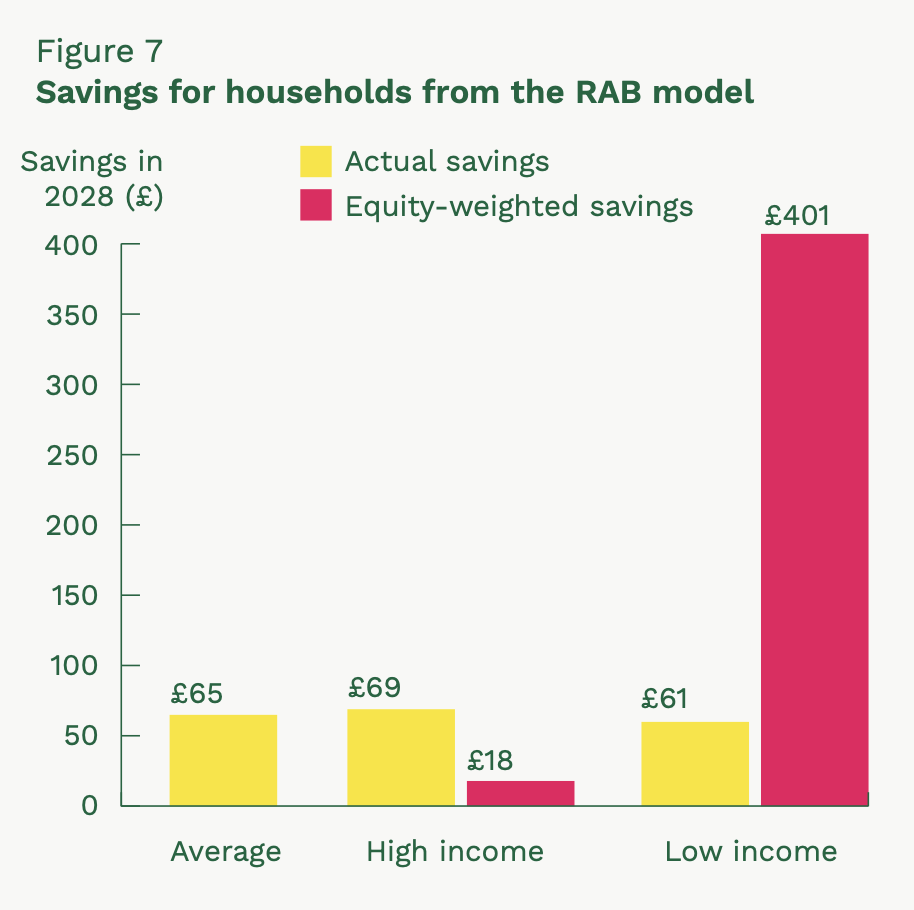

We estimate that the RAB would save the average household £65 per year as soon as 2028, which is equal to £1.7 billion in total.³⁴ The impact of this differs across income groups, as an additional pound of income is worth more to a low-income household than it is to a high-income household. For the bottom 10% of households this saving represents 0.7% of annual disposable income, whereas for the average household it represents 0.1%.

Consequently, we also calculate the equity-weighted savings across deciles using a government-approved approach, which reflects the higher relative value of these savings to lower-income households.³⁵ For example, we calculate that the RAB will save the bottom 10% of households £61 in 2028 (because of lower energy use), but in equity-weighted terms this is worth £401. Conversely, the top 10% are expected to save £69 in 2028 (because of higher energy use), but this is worth less in equity-weighted terms, at £18.

Savings for businesses

We estimate that the RAB will save businesses £3.3 billion in 2028. Cafés and pubs, specifically, are expected to benefit significantly from the RAB proposal. Pubs would save £38 million in 2028 and cafés would save £9 million in 2028. This is the equivalent of £850 for an average pub and £820 for an average café.

Savings for industry

The £3.3 billion savings for businesses includes savings for industry. For example, in 2028 we estimate the RAB to save the iron and steel industry over £67 million, the chemicals industry £128 million, and ceramics and other minerals (e.g. glass and cement) £37 million.

Activists reveal artwork on Port Talbot beach, calling on the government to support a just transition for steelworkers.

Savings for industry and businesses will also be passed on to consumers via lower inflation, further alleviating the cost of living crisis.

Savings in a global gas price spike scenario

As well as providing immediate relief to billpayers, this RAB proposal would also act as an insurance policy, protecting families and businesses against the threat of future international gas price spikes.

Even larger savings than those outlined above would have occurred had gas plants been under a RAB during the 2021–22 gas crisis, when wholesale gas costs skyrocketed. We estimate a RAB would have prevented an additional £8.9 billion being added to bills in 2021 alone, which equates to £155 per household.

Over the years, many solutions have been put forward to address the issues facing the electricity system. Below, we discuss some of these other proposals to curtail the power of gas plants to dictate electricity prices and extract rent from households and businesses.

Zonal pricing model

One solution that has been consulted on is changing the market mechanism from a ‘pay-as-clear’³⁶ model to a zonal pricing model. This would involve splitting the UK into multiple geographical zones and essentially having a marginal cost stack for each zone. In practice, this would mean that areas with high cheap renewable capacity would pay lower prices, and areas with less cheap renewable capacity (and constrained capacity to import renewable energy from other zones) would pay the higher prices set by gas. This would make gas the marginal generator only in areas where it is truly marginal, limiting its cost impacts to regional rather than national level. However, the government has recently ruled out this approach amid fears that such a major market reform would lead to increases in capital costs.

Splitting the market

Splitting the market into separate low-carbon and fossil auctions has also been discussed. In this scenario, renewable prices would be paid for renewable energy and these would not be directly impacted by inflated gas prices. While on the surface the concept has potential, it faces significant challenges. Clean energy still requires high upfront capital investment and stable revenue through long-term contracts, which are currently underpinned by the integrated market. A split market would create uncertainty, disrupt existing contracts and undermine investor confidence – ultimately raising the cost of capital for new projects. Without a mechanism for managing these risks, and in the absence of large-scale storage or flexible demand to balance the system, the operational and transition costs of creating a two-tier market outweigh the benefits.

Shifting levies

Taking policy levies off electricity bills and putting them onto gas bills or general taxation has also been suggested. The main benefit of this reform lies in correcting an injustice: despite electricity becoming cleaner, electricity bills are artificially expensive because they bear the costs of decarbonisation, while gas bills remain relatively cheap, undermining the energy transition. Shifting levies onto gas bills would lower electricity bills, encourage electrification and better align prices with carbon intensity. However, this approach has political drawbacks. Raising gas prices during a cost of living crisis is unpopular and, more importantly, it does not directly address the investment gap in low-carbon generation with controllable output. While shifting levies to gas would rebalance incentives to help accelerate electrification, it is unlikely that it would reduce bills overall, and the net household cost burden is likely to remain the same. Taking levies from electricity bills into general taxation would make electricity cheaper while avoiding the issue of increasing gas prices, and we would encourage the government to look into this alongside our RAB proposal.

Our RAB proposal addresses the distorting market power of gas plants while ensuring that gas is part of the strategic energy reserve. This option can be delivered at a lower political cost and with better returns for billpayers than most of the alternatives discussed above, and we therefore recommend that the government rapidly implements this policy.

Conclusion

The UK’s current electricity pricing model – where gas power largely determines the wholesale price of electricity – has led to persistently high energy costs. This structure has exposed the energy system to significant volatility, especially during periods of global disruption such as the 2021–22 gas price crisis.

While significant and commendable progress has been made in deploying renewable energy, the full economic benefits of this transition are not being realised under existing market arrangements. Tackling this problem is not only desirable – it is increasingly politically and socially urgent.

Our recommendation is to bring gas plants into a Regulated Asset Base. This would prevent them from extracting scarcity rents during periods of high demand, while retaining these plants as part of a strategic reserve to support system reliability.

This policy could be delivered in two years’ time without the need for new primary legislation. With gas plants quickly becoming stranded assets in the transition to clean energy, this offer of secure and regular returns could be very attractive to many plant operators.

Our modelling suggests that this approach could reduce average household energy bills by approximately £65 per year in 2028, and generate significant cost savings across the wider economy. Alongside additional policy proposals from other civil society groups, such as E3G and EnergyUK, our recommendation goes a long way to reaching the government’s goal of £300 savings per household, per year.³⁷ It also insures families and businesses – and the public purse – against the extraordinary spikes in fossil fuel prices that have sparked half of the UK’s recessions since the 1970s.³⁸

The longer the current pricing model remains in place, the greater the cost to consumers, the economy and the climate. Aligning market design with the goals of affordability, resilience and decarbonisation will position the UK as a world leader in the energy transition, while delivering tangible benefits for households, businesses and industry alike.

Methodology

Stonehaven modelled the impact of taking gas power plants out of the wholesale electricity market and, instead, giving gas plants a regulated revenue. The savings come from:

- Lower wholesale market prices.

- Lower balancing costs, as gas plants no longer have market power.

- Lower carbon costs. The model assumes that gas power stations no longer pay for UK ETS credits or the Carbon Price Support, reducing the RAB payments needed to cover gas costs.

The costs come from paying fuel costs, maintenance and anticipated returns to the owner via the RAB, recovered from consumer bills.

The analysis assumes gas prices at cost in the balancing market. It excludes the cost of having to ‘ramp-up’ production at short notice to help with balancing. It also does not look at the impact of other technologies gaining and exploiting the market power that gas currently has. These would reduce consumer savings.

Costs

The value of the RAB is calculated as the product of total installed gas capacity and the capital and fixed cost per MW (over £73,000), assuming a load factor of 93%.³⁹ The model assumes this figure of £17 billion would be spread evenly over 20 years, and the in-year value would be added to consumer bills. The cost per household is calculated using projections of residential and total electricity consumption from DESNZ’s Energy and Emissions Projections reference scenario, and the number of households from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Annual fuel costs are calculated similarly using the respective Levelised Cost of Energy (LCOE) component value, which is then converted to £/MW (£350,000/MW).

Wholesale market impact

The effect of removing gas from the wholesale market is modelled by calculating the potential savings from importing cheaper electricity from interconnected markets. For each settlement period between July 2016 to June 2025, the model examines hourly prices across interconnected markets; it assumes the UK would import from all with prices below the UK’s price, and export to those with prices above the UK’s price. That means the marginal importer is the most expensive connected market of those cheaper than the UK. Potential savings are calculated as the difference between the marginal interconnected price and the UK wholesale price for each period.

The average percentage savings achievable by importing electricity at lower prices is calculated using the average potential savings and average UK wholesale price over the time period. The model applies this percentage savings to the projected demand of in-scope electricity (which excludes existing and forecasted CfD generation and gas) and uses the Energy and Emissions Projections reference scenario for wholesale prices and retail prices from the Green Book to calculate the bill savings. For forecasted generation, the model takes an average of new wind and solar as well as gas from NESO’s Future Energy Scenarios (FES). The total wholesale market savings is calculated as:

Balancing market impact

The model uses historic balancing action data to calculate the average price received by gas plants in the balancing market from 2021 to 2025.

The price impact in the balancing market (BM) is calculated as:

Where potential savings is:

The model calculates the savings in balancing costs by applying the price impact to projections of balancing costs in NESO’s 2025 Annual Balancing Costs Report.

Carbon costs impact

Potential savings from carbon costs are calculated using projections of UK ETS prices and gas generations from FES.

Total impact

The total net savings is the sum of the wholesale market savings, balancing market savings and carbon cost savings.

Impact of RAB in 2021

To calculate the potential savings of the RAB in 2021 the same methodology outlined above is used, with three key changes:

- When calculating the impact on the wholesale market, the model restricts the analysis of the settlement periods to those in 2021. Gas prices began to rise in 2021 well in advance of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This was driven by market conditions, and 2021 is therefore more representative of a typical spike in gas prices.

- The same change is made in calculating the price impact in the balancing market.

- To calculate carbon cost savings, the model uses historical data on UK ETS prices and gas generation.

Savings

Household savings are calculated using the same approach to household costs outlined in the Costs section above. The distributional analysis is achieved by breaking down total household savings into equivalised⁴⁰ disposable income deciles.

This disaggregation is done using estimated household electricity consumption to derive each decile’s share of total consumption. Average electricity consumption is calculated using average electricity expenditure by decile, as provided by the ONS, as well as average fixed and variable costs from Ofgem. Average savings per household in each decile are calculated using the number of households per decile in the ONS Living Costs and Food (LCF) Survey.

Equity-weighted results are calculated by multiplying average savings with equity weights for each decile. These weights are calculated according to Green Book guidance, using the following equations:

Total savings for businesses were calculated by subtracting total savings for households from the total impact of the RAB. The model calculates sector-specific savings using the price impact of total savings expressed in £/MWh. The model uses the 2023 electricity consumption for each sub sector⁴¹ as a baseline to which the price impact is added.

References

- CBI (24 February 2025) Growth and innovation in the UK’s net zero economy. https://www.cbi.org.uk/articles/growth-and-innovation-in-the-uk-s-net-zero-economy/

- ONS (1 February 2022) Energy prices and their effect on households. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/energypricesandtheireffectonhouseholds/2022-02-01

- MoneySavingExpert (updated 8 July 2025) What is the Energy Price Cap? https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/utilities/what-is-the-energy-price-cap/

- ECIU (20 February 2025) Russian invasion anniversary: £140bn gas bill for UK since crisis began. https://eciu.net/media/press-releases/2025/russian-invasion-anniversary-140bn-gas-bill-for-uk-since-crisis-began

- H. Ritchie (15 August 2023) If the UK has lots of renewables, why do electricity prices follow gas prices? https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/electricity-pricing

- Most up-to-date figures from 2021. In Zakeri, B. et al. (2023) The role of natural gas in setting electricity prices in Europe, Energy Reports, Vol 10, pp. 2778–2792. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352484723013057

- Carbon Brief (20 May 2025) Factcheck: Why expensive gas – not net-zero – is keeping UK electricity prices so high. https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-why-expensive-gas-not-net-zero-is-keeping-uk-electricity-prices-so-high/

- J. Ambrose (8 January 2025) Two power station owners to get more than £12m for three hours of electricity. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/jan/08/two-power-station-owners-to-get-more-than-12m-for-three-hours-of-electricity

- R. Miller (23 July 2025) UK raises guaranteed maximum electricity price for wind developers. https://www.ft.com/content/73ae2ec5-c274-411e-8757-d22d79c24aa0

- National Energy Action (n.d.) Energy Crisis. https://www.nea.org.uk/energy-crisis/

- GOV.UK (11 November 2020) Health matters: cold weather and COVID-19. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-cold-weather-and-covid-19/health-matters-cold-weather-and-covid-19

- Ibid.

- BRE Group (1 March 2023) Tackling cold homes would save the NHS £540mn per year, new BRE research reveals. https://bregroup.com/news/tackling-cold-homes-would-save-the-nhs-540mn-per-year-new-bre-research-reveals

- Bennet Institute for Public Policy (10 January 2022) Boosting low incomes is vital for levelling up. https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/blog/levelling-up-income/

- ONS (19 May 2025) The impact of higher energy costs on UK businesses: 2021 to 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/output/articles/theimpactofhigherenergycostsonukbusinesses/2021to2024

- UK Steel (2 September 2024) New report: Opportunity for Government to reduce electricity prices to uplift steel industry. https://www.uksteel.org/steel-news-2024/opportunity-for-gov-to-reduce-power-prices-uplift-uk-steel

- R. James (1 May 2025) Almost £100 million spent on British Steel nationalisation so far, minister says. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/jonathan-reynolds-british-steel-scunthorpe-secretary-of-state-north-lincolnshire-b1225409.html

- GOV.UK (22 June 2025) Powering Britain’s future: Electricity bills to be slashed for over 7,000 businesses in major industry shake-up. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/powering-britains-future-electricity-bills-to-be-slashed-for-over-7000-businesses-in-major-industry-shake-up

- Office for Budget Responsibility (2023) The cost of the Government’s energy support policies. https://obr.uk/box/the-cost-of-the-governments-energy-support-policies/

- Ipsos (22 April 2025) Almost nine in ten Britons are concerned about energy prices. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/almost-nine-ten-britons-are-concerned-about-energy-prices

- GOV.UK (27 March 2025) Accredited official statistics: Provisional UK greenhouse gas emissions statistics 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/provisional-uk-greenhouse-gas-emissions-statistics-2024

- F. Mayo (9 August 2024) The largest emitters in the UK: annual review. Ember. https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/08/The-largest-emitters-in-the-UK_-annual-review-1-1.pdf

- Climate Change Committee (26 February 2025) The Seventh Carbon Budget. http://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/the-seventh-carbon-budget/

- Climate Change Committee (25 June 2025) Progress in reducing emissions – 2025 report to Parliament. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/progress-in-reducing-emissions-2025-report-to-parliament/

- Ibid.

- Climate Change Committee (25 June 2025) Make electricity cheaper for consumers, says climate advisor. https://www.theccc.org.uk/2025/06/25/make-electricity-cheaper-for-consumers-says-climate-advisor/

- See Costs section in Methodology.

- See Costs section in Methodology.

- Ofgem. Energy price cap (default tariff) levels. https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/energy-policy-and-regulation/policy-and-regulatory-programmes/energy-price-cap-default-tariff-policy/energy-price-cap-default-tariff-levels

- A. Khan, C. Hayes and M. Lawrence (27 April 2025) Nationalise Gas to Lower Bills: How a Public Strategic Reserve Can Lower Costs and Enhance Energy Security. https://www.common-wealth.org/publications/nationalise-gas-to-lower-bills

- See Costs section in Methodology.

- Climate Change Committee (26 February 2025) The Seventh Carbon Budget. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/the-seventh-carbon-budget/

- See Balancing market impact section in Methodology.

- This figure has been rounded to the nearest multiple of 5. All savings are in 2023 prices. Household and business savings may not sum to total savings due to rounding.

- HM Treasury (23 August 2024) The Green Book and accompanying guidance. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/the-green-book-and-accompanying-guidance-and-documents

- Under a ‘pay-as-clear’ model, market participants pay the same price per unit of electricity, which is set based on the highest accepted bid.

- E3G (15 January 2025) The UK’s clean power mission: Delivering the prize. https://www.e3g.org/publications/the-uks-clean-power-mission-delivering-the-prize/ and Energy UK (11 March 2025) How to cut bills: A crisis we can’t afford to ignore. https://www.energy-uk.org.uk/publications/how-to-cut-bills-a-crisis-we-cant-afford-to-ignore/

- Climate Change Committee (26 February 2025) The Seventh Carbon Budget. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/the-seventh-carbon-budget/

- The load factor is taken from DESNZ’s Example LCOE Calculator.

- These are provided by the ONS Living Costs and Food (LCF) Survey. Larger households need a higher level of household income to achieve the same standard of living as smaller households. For example, a two-person household does not need as much income as a family of four to have the same standard of living. Equivalising disposable income involves applying a scaling factor to household disposable income to adjust for differences in household size and composition, and enables the comparison of impacts on households of different sizes.

- Taken from Energy Consumption in the UK statistics provided by DESNZ.