In the spacious palm-fringed oasis of M’Hamid El Ghizlane in the Moroccan Sahara, people have lived self-sufficiently for hundreds of years.

But winter rains have dried up almost completely since the 1970s in the desert enclave. As a result, agriculture is unable to provide the same levels of income and has been abandoned almost entirely. Now, the town is a starting point for tours across the desert.

Greenpeace visited and witnessed the climate change impact in one of the Moroccan oases – M’hamid ElGhizlane. © Therese di Campo / Greenpeace

It’s thought that four-fifths of Morocco’s water resources could vanish over the next 25 years. And as climate change gathers pace, different versions of this story are playing out all over the world.

Climate change is causing ever longer and more severe periods of drought. Besides this, many regions of the world lack the infrastructure to collect and sanitise water. And the high costs of private water supplies often mean that those living in poverty lack access to clean water.

Today, over 780 million people live without access to clean drinking water. The consequences of this for lives, livelihoods and quality of life of dwindling water resources are immense.

Here’s how communities worldwide are fighting for their water.

Climate change causes drought, leading to water crises across southern Africa

In South Africa, Cape Town faced such an extreme water crisis between 2017 and 2018 thanks to drought, that the term ‘Day Zero’ was coined – for when the water supply to the city effectively ran out. (It was in fact the term for when major dams supplying the city with water reached below a critical marker.)

Reaching ‘Day Zero’ would have made Cape Town the first major world city to run out of water. This would have meant extreme restrictions on water use, and queues for daily rations.

City officials launched a huge public campaign, and water use fell dramatically. Special tap devices and hand sanitiser pumps were installed across the city’s public washrooms. Capetonians learned to keep their grey (used) shower water for flushing toilets. Thirsty produce such as watercress was off the restaurants’ menus.

Water use fell dramatically to half of what it was by March 2018, to around half a billion litres a day.

Strong rains in June 2018 meant dam reserves were restored, heralding the end of the crisis.

Dwindling water supplies at Theewaterskloof Dam, an earth-fill type dam located on the Sonderend River near Villiersdorp, Western Cape, South Africa, around 100km east of Cape Town. © Kevin Sawyer / Greenpeace

Locals queue for water at Newlands Spring in Newlands, Cape Town. © Kevin Sawyer / Greenpeace

A young boy collects water from a community tap with the Matimba coal power station in the background. The Waterberg area is incredibly water-scarce, but major new coal mines and power stations are planned for the area. © Shayne Robinson / Greenpeace

Cape Town’s success at overcoming the city’s water crisis offers hope for other regions set to face water shortages in the future.

And thankfully, Africa is also a hub of environmental innovation – particularly when it comes to solar power.

Farmers in Kenya are farming using more ecological practices, increasing resilience and the ability to cope with climate change – through the use of solar-powered water pumps, for example.

Stella Muthama, an ecological farmer in Kenya, watering her spinach using a solar powered water pump. © Greenpeace / Paul Basweti

In parts of the US, clean water is a luxury for those who can afford it – which can mean corporations over communities of colour

Even in wealthy countries like the US, clean water for citizens is sadly not a given. This lack of access to a fundamental human need is one of the clearest examples of environmental racism in the US.

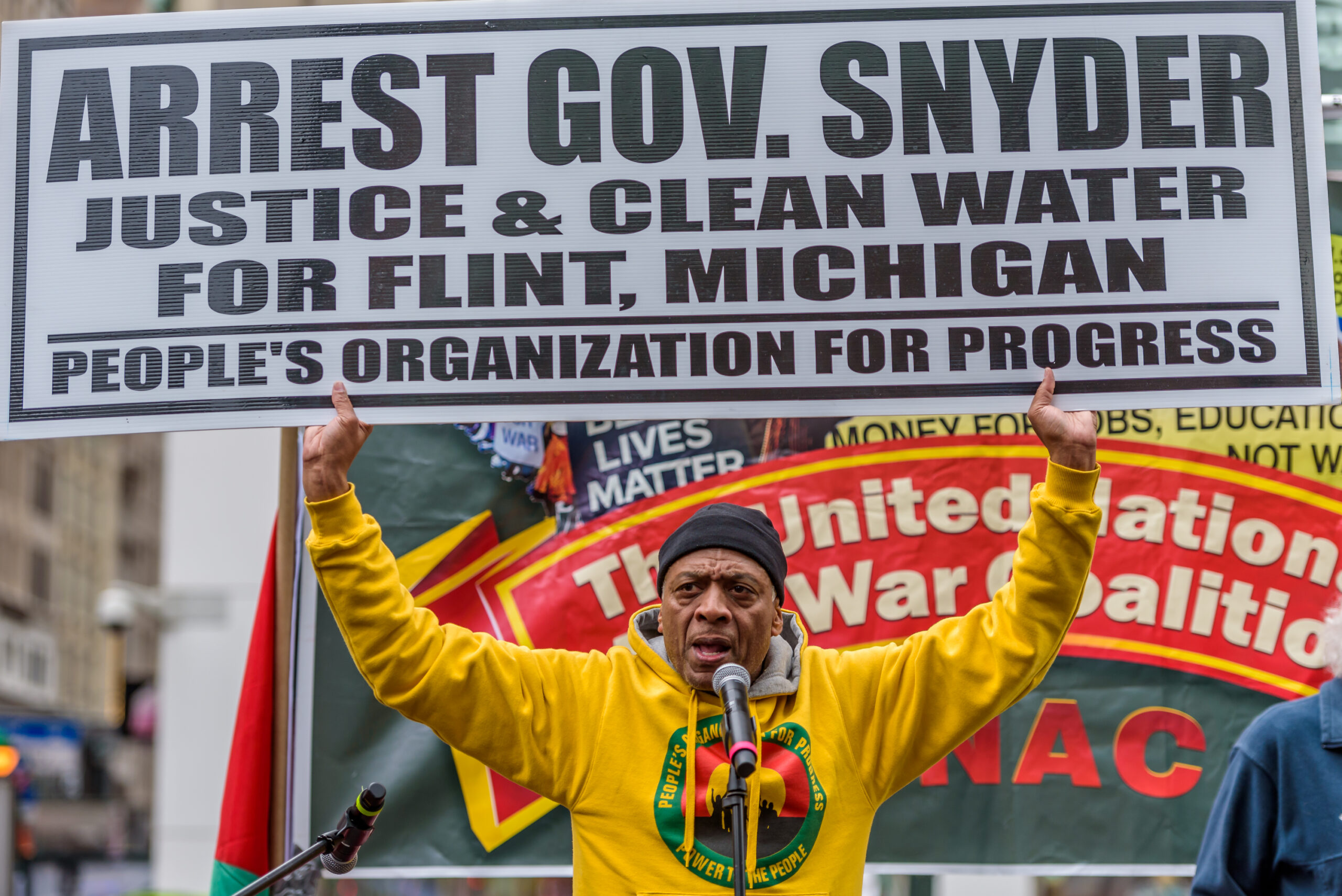

In Flint, Michigan in 2014, disadvantaged communities were left with yellow water polluted with lead coming out of their taps, after a political decision had been taken to draw drinking water from the unsanitary Flint River. The residents that were forced to drink the water were more likely to be people of colour. Because of racial and income inequality they lacked the political power to force change.

Lawrence Hamm from People’s Organization for Progress speaking at the Day of Peace and Solidarity in New York City. Organized by United National Antiwar Coalition, anti-war, anti-racist and social justice activists gathered at Herald Square in New York City, protesting against continued war and to demand money for human needs. © 2016 Erik McGregor

And there are some places in the world’s mightiest economy that tap water simply isn’t available.

In New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, many within the Native American Navajo Nation (the largest federally-recognised sovereign tribe in the US with a population of over 200,000) lack access to the most basic services – including water.

Up to 40 percent of Navajo Nation households don’t have clean running water, and are forced to rely on weekly or daily visits to water pumps. The problem is so significant that generations of families have never experienced indoor plumbing.

In attempts to rectify this, the Navajo Water Project has been working on Navajo lands in New Mexico since 2013.

Darlene Arviso is reflected in a mirror as she drives a water truck to deliver water to members of the Navajo Nation on June 06, 2019 in Thoreau, New Mexico. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images) 2019 Getty Images

Nancy Bitsue, an elderly member of the Navajo Nation, receives her monthly water delivery in the town of Thoreau, New Mexico. The Navajo native reservation consists of a 27,000-square-mile area of desert and high plains in New Mexico, southern Utah and Arizona. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images) 2019 Getty Images

The Navajo Water Project, a nonprofit from the water advocacy group Dig Deep, has been funding a mobile water delivery truck and digging and installing water tanks to individual homes. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images) 2019 Getty Images

Rising temperatures associated with global warming have worsened drought conditions on Navajo lands over recent decades.

California is another part of the US that has faced prolonged drought in recent years. But one company has continued to extract California’s water – to sell in plastic bottles.

In 2015, Nestlé extracted 36 million gallons of water from a national forest to sell as bottled water. Nestlé kept drawing water to bottle even as Californians were ordered to cut their water use because of a historic drought in the state.

Activists protest outside a Nestlé water-bottling plant where they demanded that the company halt its water-bottling operations in response to the state’s drought in Los Angeles, California in May 2015. A simultaneous rally was held at a plant in Sacramento amid California’s fourth year of drought. (Photo by FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP via Getty Images)

Climate change is bringing severe water scarcity to all corners of the globe – but innovations in water use may be able to help

From India to Africa, Europe to Australia – there is almost no part of the world that will remain unaffected by both climate change and its impacts on water supplies.

Fortunately, smart solutions are available. From desalination plants that turn sea water into fresh, to farming techniques that reduce contaminated water running out into special coastlines, water is finally getting the treatment it deserves.

It’s clear that water and a safe and stable climate are what the world has in common. Both are at risk.

Khomnal village of Mangalwhedataluka, Solapur district in Maharashtra, India, has a population of about 1600. The drinking water bore wells and hand pumps provided by the Gram panchayat are still functional but the low yield from these water sources. The dependence of a large number of families on just one or two hand-pumps of the village indicates that the water scarcity is quite high in this village. © Subrata Biswas / Greenpeace

Drought in the Barrios de Luna water reservoir.Greenpeace has documented some of the effects of the severe drought that is being experienced in Spain – the result of not only lack of rain but also of poor water management and waste of water resources. © Pedro Armestre / Greenpeace

An Indian worker inspects a pumping station at a sea water desalination plant on the outskirts of Chennai in June 2019. Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Edappadi Palaniswami has laid a foundation stone for a second unit of a desalination plant near Chennai, with a capacity to treat 150 million litres of sea water a day to make drinking water for the city that has been experiencing a severe shortage of fresh water as its reservoirs ran dry. (Photo by ARUN SANKAR/AFP via Getty Images)

To protect marine life along the coast line, farmer Gary Spotswood of Queensland Australia, has installed pumps to collect the runoff water on his 430 acres, which he then filters through aquatic plants that grow in the adjacent wetlands. In the quest to save the Great Barrier Reef, researchers, farmers and business owners are looking for ways to reduce the effects of climate change as experts warn that a third mass bleaching has taken place. (Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images) © 2019 Jonas Gratzer