Whales are incredible creatures. They are the largest animals on earth, can be found in all oceans and play an important role in the marine environment. Warm-blooded and air breathing mammals like us, whales are our allies in the fight against climate change. Their poop fertilises the ocean, which produces large blooms of microscopic algae that absorb enormous amounts of carbon dioxide.

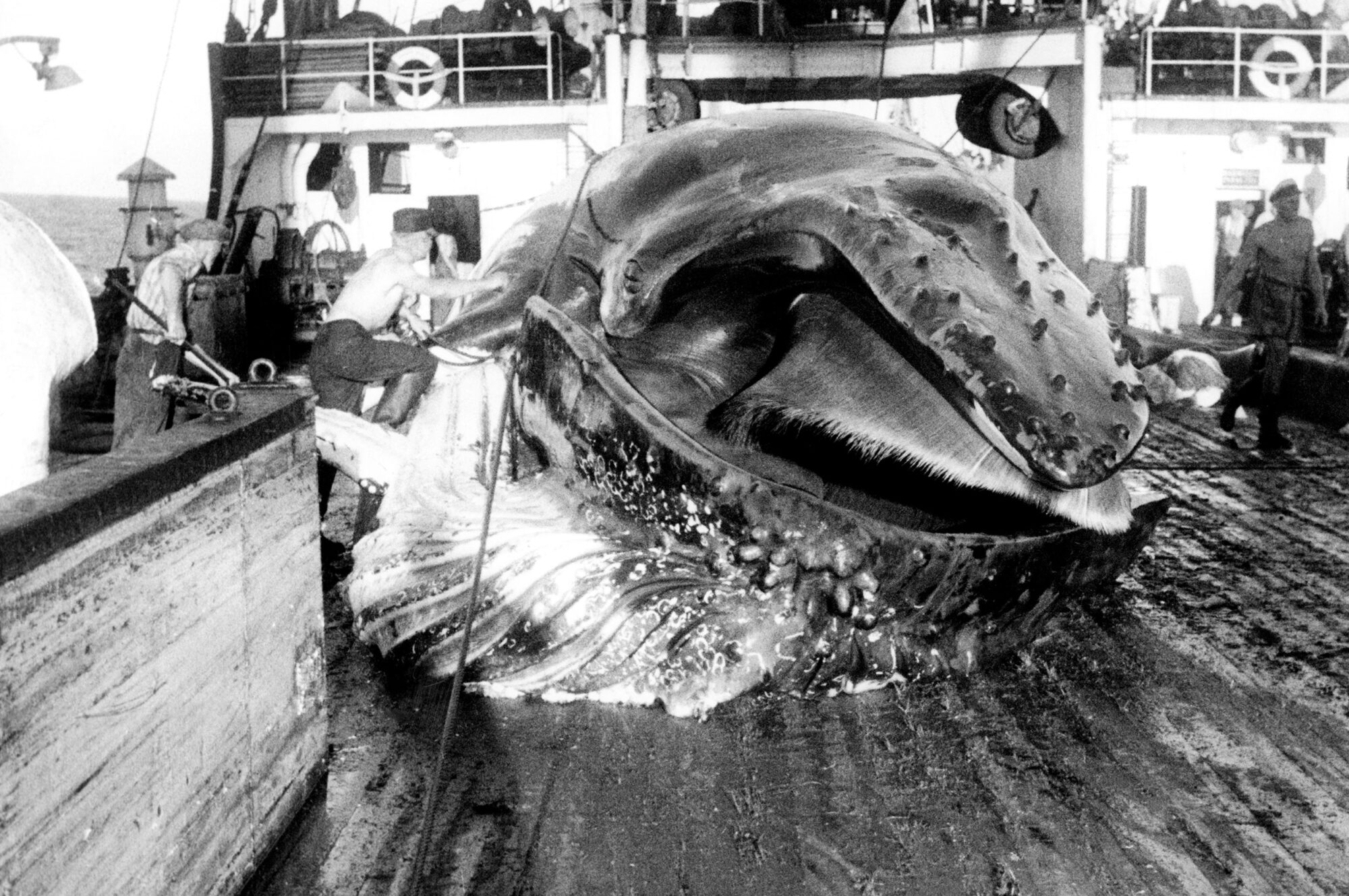

For thousands of years though, whales have been hunted for their meat, blubber and bones. But it was in the 20th century that they became hunted on a large commercial scale, because of factory ships and explosive harpoons. 50,000 whales were killed yearly by 1930, which led to a rapid decline in whale numbers.

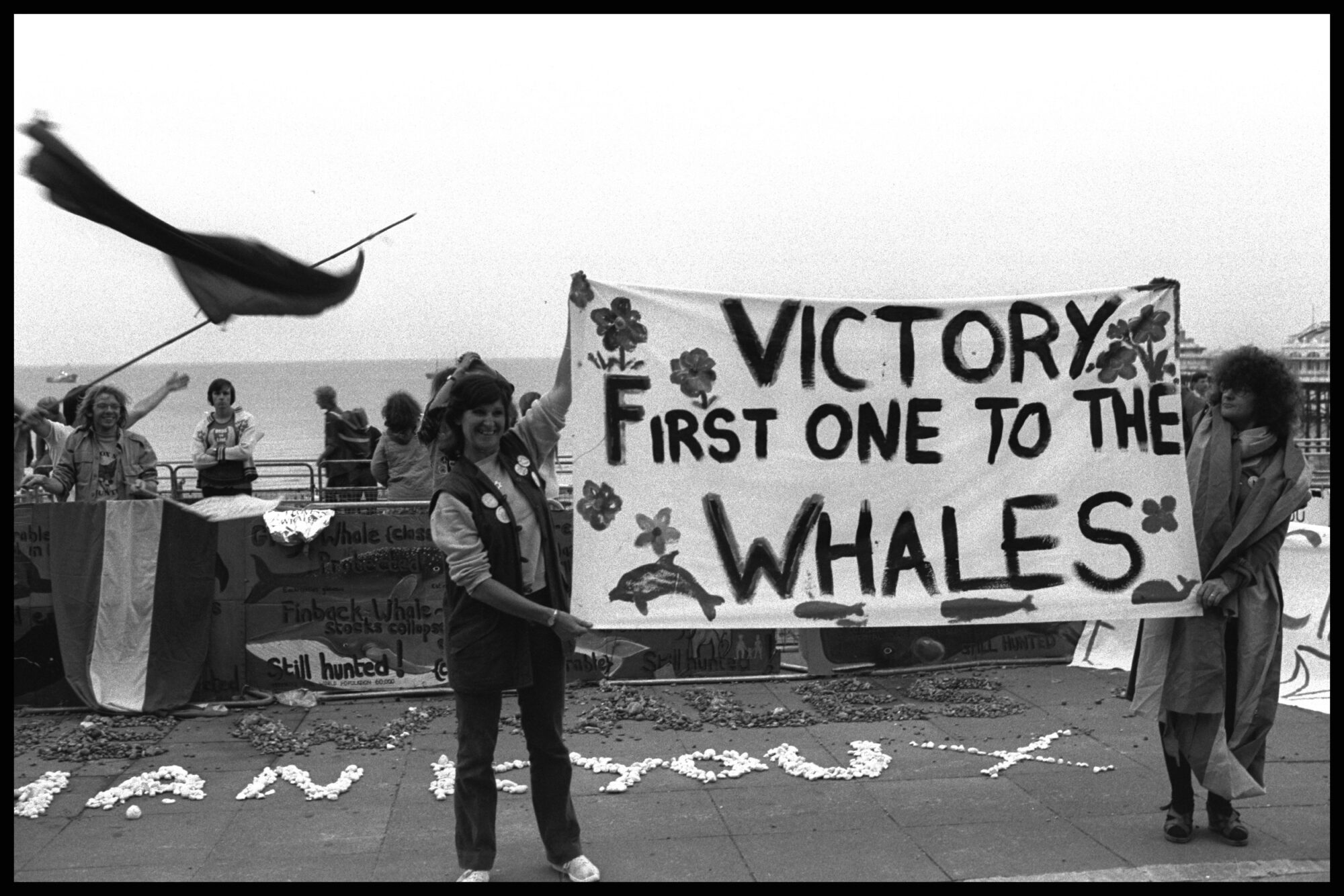

After years of high profile anti-whaling campaigns and public pressure, the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) landmark conference in Brighton in 1982 decided there should be a pause in commercial whaling. Known as a whaling moratorium, the ban allowed some types of whales to recover their populations. For example, humpback whales have made a remarkable comeback. In the mid 1950s, only 450 remained. And now their population stands at around 25,000. Likewise, a recent sighting of 150 fin whales feeding have given scientists hope for whale recovery.

Breaching Humpback Whale in the Indian Ocean, Wild Coast, South Africa 2013 Ⓒ Reinhard Dirscherl / ullstein bild / Getty

But since its announcement, the success of the whaling ban has been at risk. Both Norway and Iceland’s governments objected to it and continued to hunt. And under the pretence of scientific research whaling continued in Japan too. In 2019, Japan’s government left the IWC and began commercial whaling as soon as it was no longer bound to the agreement.

These pictures illustrate the journey that led to the ban of commercial whaling and the loopholes in the moratorium. As well as what still needs to be done to save the whales and protect our oceans for the future.

1950s: commercial whale hunting

Factory ships and explosive harpoons meant that whales were hunted on a larger, commercial scale. This reduced their numbers hugely.