This is a guest post from writer and campaigner Melissa Parker

Disabled people are among the worst affected by climate change and environmental breakdown. Climate change impacts marginalised groups first, and the disabled community is the largest marginalised group.

Despite this, we’re routinely excluded from environmental decision-making. At the COP26 climate summit, Israel’s Energy Minister Karine Elharrar couldn’t get into the compound in her wheelchair-accessible vehicle. After two hours she was finally offered a shuttle to the site – which was also inaccessible. This exclusion isn’t just unfair to disabled people; it wastes everyone else’s time too.

So many disabled people are doing vital work for the planet. But our efforts are hindered by a society that often seems indifferent to our needs. I spoke to four people whose stories shed light on the frustrations of being a disabled environmentalist.

“I’ve used so much plastic just to stay alive”

When single-use plastic straws were banned from restaurants, lawmakers failed to recognise the dangers of the alternatives. Disabled people can hurt themselves with metal straws, or choke on the paper ones.

This lack of understanding frustrates Penny Pepper, an author and poet who has written about the need for plastic straws. She has tried and failed to use different straws, and feels shamed by others within the environmental movement. “I have tried 100 alternative straws, and I have tried different baby wipes before it was headline news!” She says environmentalism often targets these convenience items, ignoring the disabled people who rely on them.

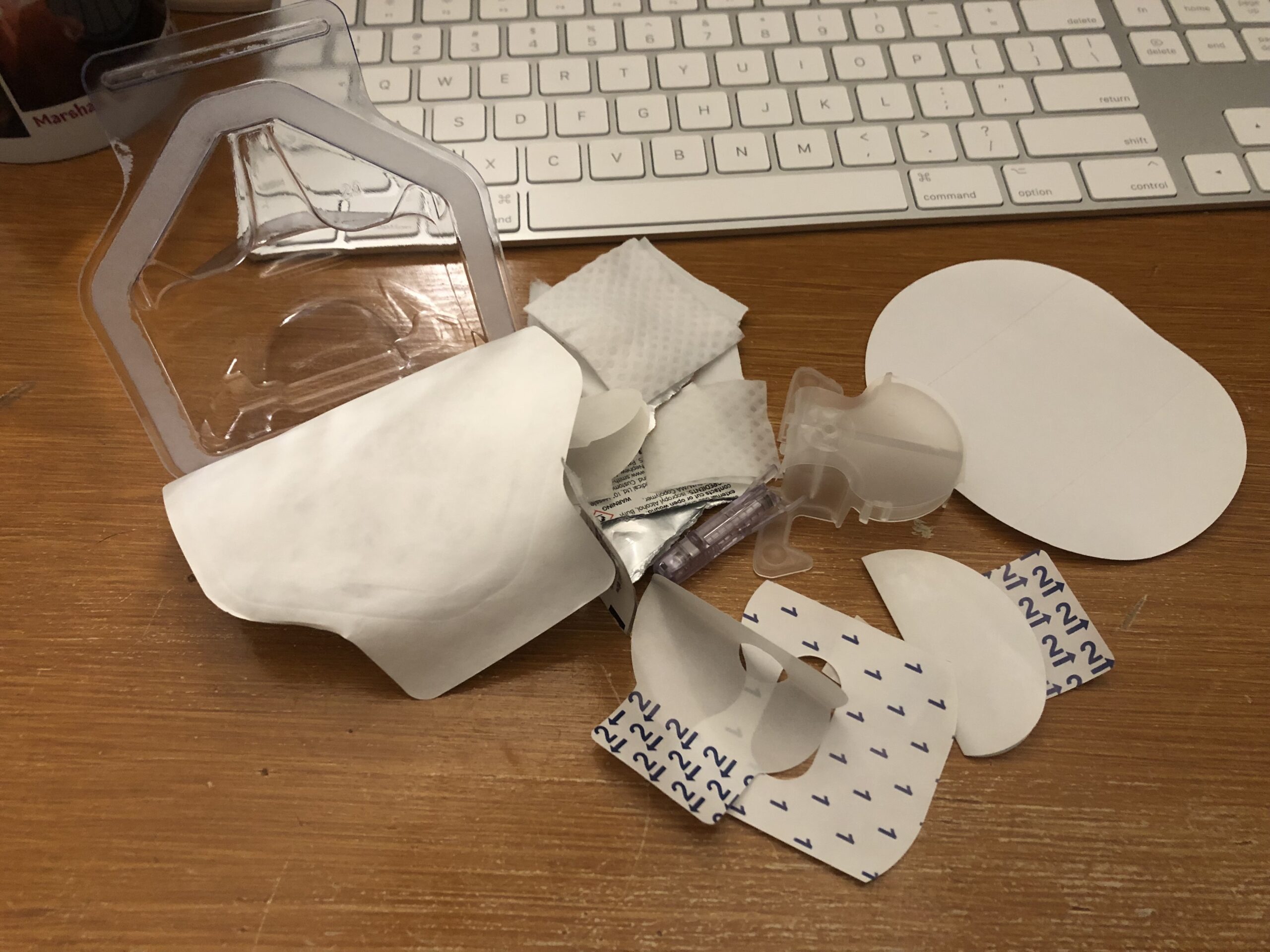

Plastic doesn’t just make disabled people’s lives easier or more independent – although that would be enough justification. Many people need it to survive. Stephanie Ash, a social work student and disability advocate, notes, “I’ve used so much plastic to stay alive. My insulin pump and diabetic supplies create so much waste. I love folks who can participate in the Zero Waste Movement, and I’m sad that I’ll never be able to.”

Packaging from Stephanie’s continuous glucose monitor, used to manage her diabetes. Stephanie Ash

Stephanie recalls a video of a person who could fit their plastic waste for the year into a single glass jar. It’s become an enduring symbol of the problem. “I thought that was wonderful, but it also felt like an indictment of my disability and what I need to stay healthy.”

She is still committed to the environmental movement. She’s reducing, reusing and recycling, composting, eating local, and going vegan. However, when she sees those glass jars she’s still haunted by the feeling that there is nothing useful she can do.

“Cycling is joyous, but I’m excluded from these routes”

Harriet Larrington-Spencer, researches healthy and active travel in Greater Manchester and is passionate about inclusive travel. Her own experiences inspired her to fight for a better transport system.

“I’ve lost a lot of activities in my life because of disability and illness, but cycling is joyous”, she says. It also enables her to complete everyday tasks and chores: “it works really well in terms of managing energy levels by not having huge outings but making the everyday fun.”

Harriet and co-pilot Frida use a tricycle to complete everyday tasks and chores. BikeIsBest

But, her experiences show that there’s still a problem with accessibility. For example, many car-free cycle routes have barriers designed to stop motorbikes. But they also stop people on non-standard cycles like trikes, people using wheelchairs and people cycling with kids in trailers. “I am then excluded from these routes, which is a really painful feeling. Local authorities know that these barriers are discriminatory, but they also know that they are ineffective.” The people on motorbikes tend to be non-disabled, so they can “manoeuvre through or around the barriers.”

Barriers like this one in Peel Park, Salford, exclude people using wheelchairs, tricycles and other mobility aids. Harriet Lannington Spencer

These barriers force disabled people onto roads, which often lack good cycling facilities because planners assume that people will use the car-free route. This puts a lot of disabled people off cycling.

Harriet describes several similar design mistakes that could have been avoided if disabled people had been involved in the original decision. For example, cycle parking needs to be near shop entrances so disabled cyclists don’t have to struggle carrying heavy bags. Excluding us from the planning process leads to avoidable problems that would be obvious to a disabled person. And over and over again, it unfairly places the onus on us to fight for change later.

“It feels like your contribution doesn’t matter”

Michael Bosley is a member of the Extinction Rebellion (XR) group Disabled Rebels. He divides his protest experience into two periods: before and after he acquired his disability. Before, he could simply jump on a train. Now he has to consider the logistics: will someone be on duty to help him onto the train? Will there be luggage blocking the wheelchair space?

Even when he attends local rallies, there can be problems. When he joined a recent street protest, the crowd pushed forward, and he was trapped by barriers and bollards, unable to move. He was soon ‘spat out’ and pushed to the back.

Despite holding a sign, and shouting to feel a connection with his fellow protestors, many refuse to make eye contact. There was a feeling of otherness he hadn’t encountered when he was non-disabled.

Michael remembers what it was like before, “it was an emotionally different experience. I was passionate about the cause, but it was also about social interaction,”. The “layers of standing people” at rallying points make it difficult to see and feel involved. “It feels like your contribution doesn’t matter, as though your disability rips your humanity out.”

On another march, he did get support from an organiser, and found an opening in the sea of backs. But he was then immediately asked to move – the space had only been created to bring a cardboard coffin to the front. Symbolism and theatrics were more valuable than inclusion. Michael recalls wondering, “why is it that you think I should move, shuffle up, for a cardboard coffin? Where’s my value?”

“It’s important we are all aware”

Alieu Touray is a social worker, a volunteer peer counsellor with Legs4Africa. As an amputee, he understands how climate change affects disabled people’s quality of life, and works to raise awareness.

Legs4Africa is a charity that recycles prosthetic legs that would otherwise end up in landfills. Environmental issues aren’t always top-of-mind for the people they work with and support in sub-Saharan Africa. But changing rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, and more extreme weather have driven food insecurity, poverty and displacement in the region.

Welcome back to school and work everyone 😁

Oh, and happy 2022 of course 🌻 #welcomeback #firstday #january #2022 pic.twitter.com/LMOuaPRGY2

— Legs4Africa (@Legs4Africa) January 4, 2022

Disabled people are bound to be as affected, often more so, by these conditions, as they struggle to get the proper support for their needs. Alieu encourages the disabled people he supports to think about the environment, alongside the other things which matter to them. “To make and encourage people to get involved in environmentalism can be done in many ways – sensitising, advocating and by shining a light on problems and challenges in amputee community meetings. It’s important we are all aware.”

Fighting to live a normal life

Harriet has been able to effect real and vital change, using her Twitter presence to help get barriers changed or removed. Still, I’m struck by her words, “I just want to be able to go to the shops or cycle to work, or the park to walk my dog.”

The onus is always on disabled people to fight for better – to be activists, protest, and be proactive in the face of discrimination – just to live a normal life.

If disabled people were included in environmental decision-making from the beginning, we wouldn’t need to point out problems and mistakes almost daily. We wouldn’t have to commit radical acts to live ordinary lives. Our worth – and our value to the cause – shouldn’t be defined by how much or how little we can put in a glass jar. Nor should it matter less than the theatrics of a cardboard coffin.

You can follow Melissa on Twitter here. Guest authors work with us to share their personal experiences and perspectives, but views in guest articles aren’t necessarily those of Greenpeace.