This is a guest post from journalist, PhD researcher and founder of Sheffield Environmental Movement, Maxwell A. Ayamba.

When I co-founded 100 Black Men Walk for Health Group in 2004, little did I know that we’d make a political statement. The group’s aim was modest: to “walk and talk” in the English countryside for our health and wellbeing. But we quickly found that a walk in the countryside also meant reclaiming our rights to roam the land.

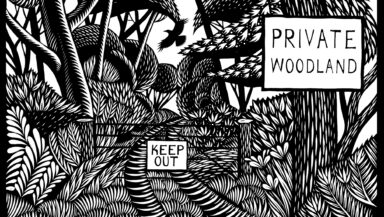

To many of Britain’s nearly eight million ethnic minorities, the British countryside still appears something of a middle-class white space. A classic symbol of ‘white British national identity’. Its access limited to a privileged class, who have the means and resources to enjoy the physical and mental benefits of getting outdoors.

This pastoral image of Britain is rife with exclusion and nurtures a limiting narrative: that Black people aren’t interested in nature. But that story simply isn’t true.