Deep in the Brazilian Amazon, the ancestral land of the Karipuna People should be a safe haven for the people, plants and animals that call it home.

Nestled up against the border with Bolivia, with its winding rivers and lush green rainforest, the land has been home to the Indigenous Karipuna for centuries.

The meeting of the Jaci Paraná River and Formoso Rivers. The Karipuna Indigenous Land is located in the municipalities of Nova Mamoré and Porto Velho, in Rondônia state, Brazil. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

To the Karipuna, the land isn’t just their home – but all of history

The Karipuna live together in one big village called Panorama, near the banks of the Jaci Paraná River.

Panorama, the village of the Karipuna indigenous people, is located at the margins of the Jaci Paraná River, northeast of their territory. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

Here, like in many Indigenous communities in the Amazon, life is organised around the river – a crucial thoroughfare, long predating roads, for transporting humans and goods.

As well as being places to fish, wash, play and gather – rivers often play a central role in an Indigenous People’s customs and traditions.

The nearby rivers weave through the surrounding landscape of dense rainforest – untouched except by those that have looked after this land for as long as anyone can remember.

Panorama Village. A Karipuna boy diving in the Jacy-Paraná river. © Tommaso Protti / Greenpeace

From living on the same land generation after generation, Indigenous communities like the Karipuna have intimate knowledge of the creatures and plant life living within their midst.

Scarlet macaw (Ara macao) in the Karipuna Indigenous Land. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

Dusky Titi Monkey, found in the Amazon rainforest. © David Tipling/Universal Images Group/ Getty Images

Like many of the Brazilian Amazon’s Indigenous Peoples, the Karipuna were only relatively recently put into contact with surrounding society. They number only 58 in total, living on Indigenous-owned lands – a right that’s (at least theoretically) guaranteed by Brazil’s constitution.

Katiká Karipuna, elder, tending the community’s smallholding. Amazon Indigenous People are able to get all the food and they need from hunting, fishing and cultivating small farms. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

But invading loggers and land-grabbers don’t care about Indigenous land rights. And as the Karipuna’s land is in such a remote part of the world’s biggest rainforest, government oversight is weak.

The Karipuna defend against the destruction of nature in the name of ‘development’

Like in many places on Earth, demand for land exerts enormous pressure on people and nature. In the Brazilian Amazon, economic development often happens by destroying the rainforest for natural resources like wood, minerals or to grow agricultural products like meat or soya.

André Karipuna shows a tree illegally removed from the territory of his people, which should be protected by the Brazilian state. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

And not only do governments like Brazil’s tolerate invasions and land-grabbing in the name of development – they often actively encourage the invaders.

In practice, that means Indigenous Peoples are constantly having to fend off incursions from people who want to steal resources or clear native trees and farm on their land.

Andre Karipuna in an illegally deforested area inside the Karipuna reserve during a patrol. The Karipuna territory is facing one of the highest rates of deforestation of all indigenous areas in the Amazon. © Tommaso Protti / Greenpeace

As Adriano Karipuna, leader of the Karipuna Indigenous People, says of the struggle: ‘We have been fighting against the destruction of our territory for a long time, so we urge the authorities to reject and repress organised crime that cuts down our forest’.

Leader of the Karipuna Adriano Karipuna in New York attending the United Nations’ Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, to address the serious threats the Karipuna people face through deforestation. At the Forum, Adriano Karipuna reports illegal invasion of their traditional, demarcated and officially protected land, stealing of timber, sales of land plots and illegal miners. He calls on the international community and the Brazilian government to fulfil its duty and protect Indigenous Peoples and their rainforests. © Luiz Roberto Lima / Greenpeace

As well as being a disaster for the Karipuna, this kind of ‘development’ in the Amazon – that values financial profit and economic growth above anything else – is a disaster for the whole planet.

The Karipuna are determined to defend the only home they have ever known. And, despite being few in number, what they have achieved is incredible.

Using a combination of long-held traditional knowledge of their territory, new forest-monitoring technology, and a solid understanding of their legal rights – they are winning their land back.

Their success, backed by Greenpeace and a Brazilian NGO called CIMI, is also a sign of growing global solidarity with Indigenous Peoples, as they come under ever-greater threats.

(L-R) Volmir Bavaresco, leader of the indigenous council CIMI, Jose Luis Cassupa, coordinator of the Indigenous organisation Opiroma and Adriano Karipuna. The sign reads ‘Everyone for the Amazon!’. © Kevin McElvaney / Greenpeace

The Amazon and its Indigenous Peoples are under threat more than ever

Threats to Indigenous Peoples in Brazil have been very real since European colonists first arrived in the 1500s. Five centuries on, they are arguably graver than ever.

This is in no small part due to the far-right government of President Jair Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro himself has complained that too many of Brazil’s Indigenous People survived the European conquest, and that too much land is set aside for them in the Brazilian constitution.

This attitude still echoes through some sections of Brazilian society – that the land should be opened up for any Brazilian to do with as they please.

This means an increase in invasions and land-grabbing – often bringing violence and disease to which Indigenous Peoples have little immunity, including now of course Covid-19. For the Indigenous Peoples themselves, this adds up to a slow-motion disaster that some have likened to a genocide.

As well as regressing on Indigenous Peoples’ human rights, the shocking fires crisis of both 2019 and 2020 show clearly that the Amazon rainforest is close to breaking point.

A fire burns in the distance. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

Many of the Indigenous Peoples that call these forests home have not escaped the dangers. As well as the grim prospect of trying to survive in a dying landscape, fires cause respiratory illnesses, which only add to the horrors of Covid-19 – which is killing many in their communities.

For the Karipuna, the threat is more subtle than raging fires all around – for now.

Still, by 2019, over 11,000 hectares of the Karipuna Indigenous land had been destroyed. This is not as much by the terrifying use of fire by farmers, as in the southern Amazon, but by loggers and land-grabbers cutting roads through forests and removing trees to sell for their wood.

Deforested areas surround a new road created by invading loggers in the Karipuna Indigenous Land. © Christian Braga / Greenpeace

Land-grabbers even started brazenly putting deforested ‘lots’ of land up for sale.

This is how it begins. A few dozen hectares here, another few hundred there, and the forest is ‘degraded’ – the invaders begin to break it up, bit by bit.

Loggers marked this tree for removal in Karipuna territory. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

Loggers, miners, and farmers begin to take even more wood, or minerals, or establish more small cattle ranches.

With the rainforest in scrappy dry patches, it then becomes much easier for farmers to set fires that clear thousands of acres in one go.

Over 11,000 hectares of forest have already been destroyed in the Karipuna Indigenous Land. © Chico Batata / Greenpeace

The Karipuna fight back

The Karipuna mounted a defence. It’s working. Things have begun to change.

Using a combination of their traditional knowledge of the landscape and high-tech equipment, they started monitoring in great detail what was happening to their forests.

A message of defiance created during a meeting of Indigenous leaders in Karipuna territory. © Fernanda Ligabue / Greenpeace

For the forest monitoring to work, the Karipuna’s in-depth knowledge of their land and experience of invasions is matched with forest density data collected by Greenpeace’s overflights.

The Karipuna are then able to exercise their constitutional land rights, by reporting these findings to authorities – they demand the government take legal action against invaders causing the deforestation.

Greenpeace monitors deforested areas in the Karipuna Indigenous Land during an overflight in September 2020. © Christian Braga / Greenpeace

The police have also carried out operations in response to the Karipuna’s crime reports, arresting those invading Karipuna land, as well as confiscating materials used for logging.

And now it’s clear that the brave resistance by the Karipuna – against those that would drive them off their land entirely – is working.

Between August 2019 and July 2020, 49.1% less forest was destroyed than the same period in the previous year, according to Greenpeace Brazil. The figures are expected to be confirmed by Brazil’s satellite monitoring agency.

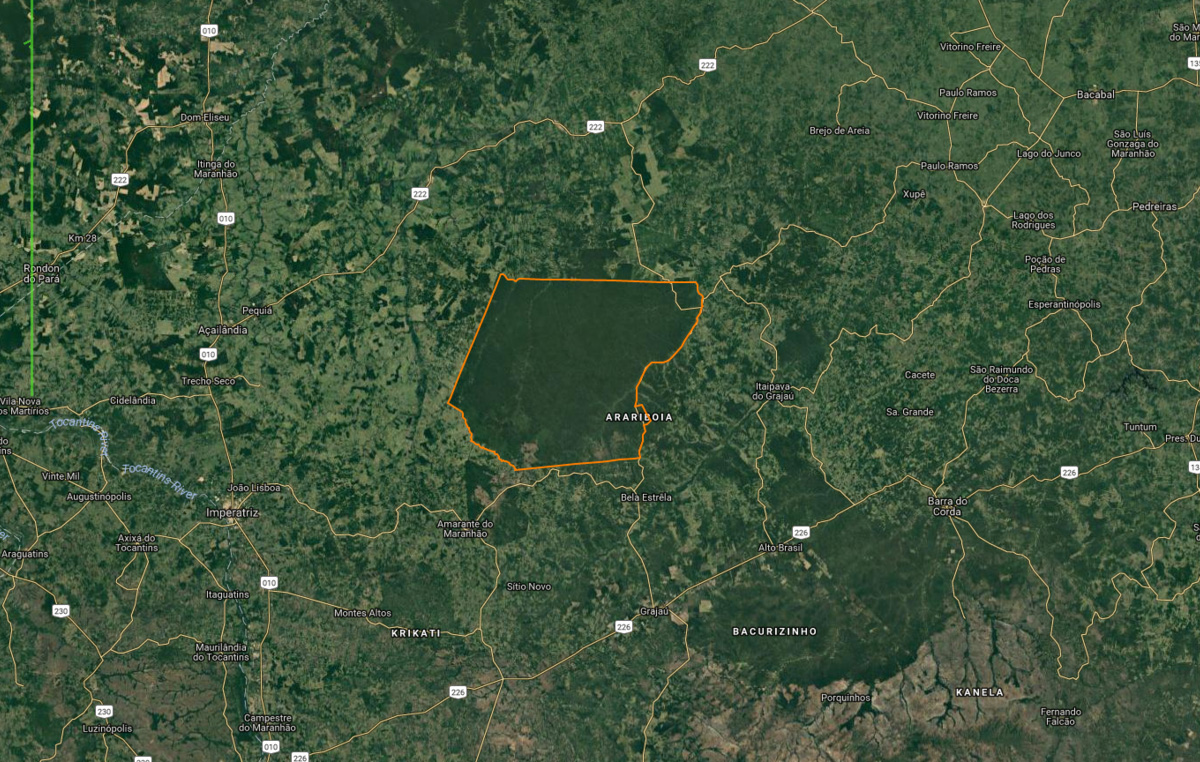

It’s long been the case that Indigenous Peoples mount the best defence against deforestation in their homelands. Other parts of the Amazon, such as the Arariboia in the northeast of Brazil, are clearly better protected thanks to the presence and protection of Indigenous forest ‘guardians’ – who sometimes sadly pay with their lives.

Image showing intact forest on the Arariboia Indigenous land in northeast Brazil. This intact area of the Amazon Rainforest is home to the Guajajara and Awá Indigenous Peoples, the latter of whom are mostly ‘uncontacted’ by mainstream society. The Guajajara Guardians help to protect the Awá from outsiders who come to log or mine illegally, particularly because they can bring disease to which the Awá have no immunity. © Google Maps.

Paulo Paulino Guajajara, a young member of the Indigenous Guajajara community, one of Brazil’s largest, was shot dead by illegal loggers on 3 November 2019 in the Arariboia Indigenous land. © Midia NINJA © Patrick Raynaud

Karipuna Leader Adriano knows it’s just the beginning of the fightback. Speaking of his people’s homelands, he said that ‘even knowing that there are still invaders in it, we hope that actions to combat deforestation continue and that we can live in peace, according to our customs and traditions’.

The Karipuna’s fight is the rest of the world’s as well

This isn’t just great news for the Karipuna – it’s good news for us all. The richness of the rainforest holds untold mysteries, from as-yet undiscovered medical miracle cures, to a key solution that would help prevent runaway climate change – natural carbon capture and storage.

Supporting Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their ancestral lands is one of the best ways to protect the forest and its biodiversity. It’s also vital in the fight against the climate crisis.

Greenpeace stands with the Karipuna and other Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. We support their demands for a permanent protection plan for the Karipuna territory, and for all Indigenous lands in the country.